Regarding my little diatribe against St. Patrick's Day, it so happens that three women in my life have told me, more or less, to chill out. And if the fairy tales we read as children have taught us anything, it's to pay attention to events that come in threes, especially when wise women are involved. I have to say that although I have been in the process of learning to chill out my whole life, and I hope that all the good aspects of this evolution will continue, I am still not great at it. In the meantime, to remind me not to take myself too seriously, I propose a little extra bit of poetry memorization, in honor of St. Patrick's admittedly honorable role in teaching the Irish to write. This fragment is the first poetry I ever remember reacting to with (to quote the author) passionate intensity; I have loved it ever since I could react to the pleasing juxtaposition of words together:

"These masterful images because complete

Grew pure in mind but out of what began?

A mound of refuse or the sweepings of a street,

Old kettles, old bottles, and a broken can,

Old iron, old bones, old rags, that raving slut

Who keeps the till. Now that my ladder's gone

I must lie down where all the ladders start

In the foul rag and bone shop of the heart."

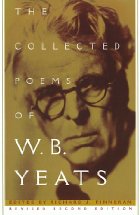

Even though W.B. Yeats wrote his own long lyrical drama cursing St. Patrick (The Wanderings of Oisin), the monk's gift of writing was certainly well used by him. This third part of "The Circus Animals' Desertion" is one of those rare verses that is equally appealing on a surface level of pleasing lingual combinations (the only level on which I was drawn to poetry when I first discovered it) AND on a level of intellectual thought and emotion now that I have grown up a little bit. At age 10, I thought the phrase "the foul rag and bone shop of the heart" was about the coolest-sounding thing I'd ever heard. Now I think it's just about the truest idea that all grand human ideas and conceits come out of the unglamorous ephemera of our existence. Sometimes we feel like we've elevated ourselves above all that, but then we have to get humble and return to our beginnings. Not often pretty, but there it is.

I love the idea of this causal connection between the refuse of a society or an individual and its grandest self-conceptions. Both categories speak to one another, are one another in some ways. It's what makes encountering a discarded Burger King wrapper while out on a hike not only disgusting but sort of melancholic as well. The grand American vista of natural beauty is all bound up with the sweeping American bent toward self-destruction and blind disregard for the world around us, often mythologized as "individualism."

Within a given person, as Spaulding Gray has pointed out, the same applies. Gray has analyzed how our demons and neuroses are inextricably bound with our best qualities, but Yeats goes even further: our grand self-conceptions and beautiful images take their nourishment and impetus from our demons and the dirty realities of our everyday hearts, combined with our desire to make something useful, lovely or complete out of the pre-existing fragments or "garbage" that's left over after we live our quotidian lives. I love how the progression of trash in the poem steadily builds in value, causing the reader to question the worthlessness of any item listed: "old kettles, old bottles, and a broken can" (well, none of that is very valuable, the reader thinks), "old iron, old bones, old rags" (bones were once a living creature, and iron and rags items of utility), "that raving slut / Who keeps the till" (surely a living person is full of value; maybe we should take another look at that broken can). And "taking another look at that broken can" is just a less graceful way of expressing the need to "lie down where all the ladders start / In the foul rag and bone shop of the heart." Personally, I feel lucky that Yeats did just that, and wrote this fitting initiation into the poetic world. I have a feeling that as I continue growing up, it will only develop new shades of beauty and meaning.