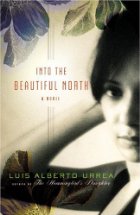

After the density of Mary Wollstonecraft and the heaviness of Mariama Bâ (to be reviewed shortly), I was in the mood for something a little light, a little frothy, with a decided sense of humor. I've seen some reviews around the blogosphere critiquing Luis Alberto Urrea's Into the Beautiful North—a quest story about three teenage Mexican girls and their gay male friend who sneak across the US/Mexican border in order to fetch back some Mexican men to repopulate their threatened town—for being lighter than expected, so I thought it might be a good match with my current mood. And indeed, I gobbled it up in three sittings, leaving not even enough time to substitute a real bookmark for the miniature subway map I grabbed hastily to mark my place. This is a novel that verges on many traps that annoy me: the quirky (overly quirky?) cast of characters, the topical references and subject matter, the heartwarming (unrealistically heartwarming?) themes and emphasis on romantic coupling toward the end—and yet, I thought it did a remarkably good job of steering clear of schmaltz and delivering a solid, entertaining tale with some thoughtful political observations thrown in for good measure.

Some reviewers have likened Into the Beautiful North to a fairy-tale, and the comparison is apt. This is no gritty portrait of hardship at the Mexican/American border, but a modern-day version of the romantic quest narrative: a fact several characters within the novel explicitly acknowledge. So, although the world depicted is not without danger, and the characters certainly feel real fear, the overall vibe is that sneaking across the border is a rollicking adventure, rather than an act of economic desperation. Protagonist Nayeli and her friends entertain passing fears of rapists in Tijuana, for example, but nobody actually comes close to injuring them—in part because of Nayeli's skills in self-defense, but also because most of the people they meet are genuinely good folks. They stay with some people who live in a garbage dump, but the dump-dwellers actually seem quite happy and comfortable. The coyote who leads them across the border is perhaps a bit shady, but only enough to provide atmosphere, not in a seriously threatening way. Nayeli and her friends fear the US Immigration agents, but those guys turn out to be basically good sorts as well. They do have to navigate racism and anti-immigration vitriol, but the narrative mitigates the harshness of these things by allowing the characters the refuge of each others' giddy, empowered camaraderie. It allows them, for example, to stand up for themselves and each other very effectively against white aggressors, without then being punished by the entrenched racism of the justice and economic systems the way they would be in, for example, a Richard Wright or Ralph Ellison novel.

I think Urrea succeeds in this perhaps unrealistically sunny worldview because his book never takes itself too seriously. Whereas the quirk and topicality factors in Middlesex hit all my annoyance buttons because I felt like it was trying too hard, Into the Beautiful North acted on me like that goofy friend at whom I just can't get mad, even at his most ridiculous. In addition to the semi-allegorical framework surrounding the book's events, there was also Urrea's delightful sense of humor, which really was the highlight of the novel, and coincidentally exactly what was missing from my reading life at the moment.

The ZZs were her favorites, and even when Matt had gone missionary on her, run off to Mexico to save the Mexicans, the ZZ Twins had hung around her house, keeping her company in his absence, keeping the bad guys at bay. They spoke that weird surfer talk that she had never quite translated. Once, when she'd asked Zemaski how he was feeling, he said, "I'm creachin' the bouf."

She had laughed for weeks about that one.

Two years later, she'd been hunting through the library's cast-off $1.00 sale table when she glanced at their computers and ventured to access the Internet. The librarian helped her search the phrase "creachin' the bouf." The best translation they could come up with was "I am a fool for the light comedic opera." She liked to think that's what Zemaski meant, though she knew it wasn't.

I quite like this little anecdote: I like her observant amusement, even in the midst of the tinge of melancholy surrounding the departure of her son and in that final "though she knew it wasn't." (Like Ma Johnston, I attempted to Google "creachin' the bouf," but couldn't figure out what it means either.)

Another unexpected pleasure about Into the Beautiful North lies in its politics: because it's so light-hearted, I think, it can get away with a level of political topicality that would feel unpleasantly preachy in a different context. In particular, Urrea includes multiple scenes underlining the fact that as the United States is to Mexico (economic oppressor, supposed land of opportunity), so is Mexico to many South- and Central-American countries. The same kind of familiar race-based vitriol thus exists on both sides of the border:

"These beans are grown here in Sinaloa," he said proudly. "The best frijoles in the world! Right near Culiacán. Then they're sold to the United States. Then they sell them back to us." He shrugged. "It gets expensive."

Tía Irma took a long time to replace the glasses in the purse.

"That," she finally proclaimed, "is the stupidest thing anyone has ever said to me."

He smiled, hoping she would not strike him with that purse.

"NAFTA," he said.

Irma stormed out of the stall and spied a Guatemalan woman picking through the spoiled fruit.

"What are you doing? she snapped.

"Provisions. For the journey north," the woman replied. She made the mistake of extending her hand and saying, "I have come so far, but I have so far to go. Alms, señora. Have mercy."

"Go back where you came from!" Irma bellowed. "Mexico is for Mexicans."

Similarly, when Mexican border agents board a bus traveling from Sinaloa to Tijuana (toward the US/Mexican border), the Mexicans joke freely about being "wetbacks when we get to the border," but a pair of illegal Colombian immigrants are manhandled off the bus and deported. Urrea takes the consistent line that the immigration hardships of the inter-Americas are caused by a broken system, and that the vast majority of individuals from any of the countries involved are decent people doing their best. Even when Nayeli and her friends are genuinely hurt by people calling them out on their illegal status (such as a pair of legal Mexican immigrants who run a diner), those people are usually presented as coming from a place of decency and honesty themselves. I appreciated this stance and agree with it in general, even if I felt the book did skate over some of the uglier, more insidious results of this kind of discrimination. This is particularly easy to do since Nayeli and company are on a transitory journey, not attempting to live long-term in the US. Ugly encounters may be scary or sad for them in the short term, but the little band never sticks around long enough to be worn down by the experience of living on the outskirts of an unwelcoming society.

But more than a political treatise, Into the Beautiful North is just a funny, effervescent little book, and one that lightened up my otherwise rather heavy January reading schedule.