Well. You know how I told you were were thinking of going to Musée de Cluny today, followed by Gallimard? You were probably having a good laugh at our expense because you probably knew it was Tuesday, and you probably remembered that most of the museums in Paris are closed on just that day of the week. We too realized it this morning in time to throw together an entirely different plan, this one involving PROUST. Lots and lots of Proust.

We started out at the Jardin des Tuileries, right across the street from the (closed on Tuesdays) Louvre. We glimpsed the distinctive glass triangle, the gargantuan palace and the crows all massing around the chimneys, but the rest will wait until later in the week. The Tuileries features lots of statuary depicting Greek and Roman mythic figures, including the one above, which I felt so accomplished for knowing was Hippodamia being abducted by the centaurs at her wedding, but it's apparently actually Hercules's wife Déjenire. So much for my knowledge of mythology.

(Just to illustrate the above point: there was also a statue in this same circle depicting Theseus slaying the Minotaur. I was like, "Who slew the Minotaur again? Was it Hercules?" And David replied, "Probably. It seems like something he'd do." "Yes," says I, "that Hercules. Always doing Herculean tasks." "Well, I suppose by definition everything he did was Herculean," David said, and I was like, "Yeah. Sometimes in the afternoon he would take a Herculean catnap, and then go for a Herculean jog." "After having a Herculean snack," David said. Etc. Ugh. It was totally Theseus all along.)

ANYhow, Jardin des Tuileries was packed. I took the standard shot up the Champs-Elysées featuring Cleopatra's Needle and the Arc de Triomphe, but it turned out to be nothing special so I won't show you. Here's a demonstration of how much I love my telephoto lens, though...

Hey Dad! Your old lens is getting a nice workout!

The Champs-Elysées grows out of the Jardin des Tuileries, and right off the garden is the little footpath and park where Proust's narrator Marcel describes coming to play as an (oddly age-androgynous) kid, and falling in love with Gilberte, the daughter of his parents' old friend and neighbor Swann. The fine people of Paris have re-named this little walkway the Allée Marcel Proust, and David and I walked along it, snapping pictures.

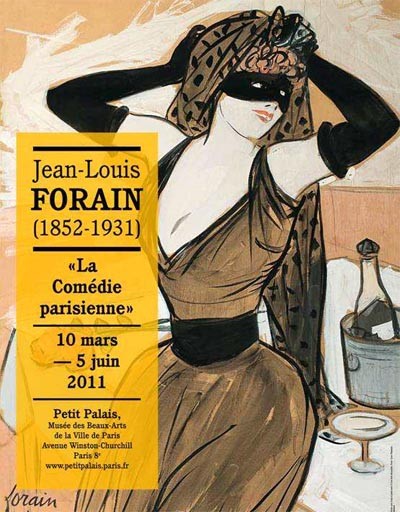

We meandered over to the Petit Grand Palais and Petit Palais, the latter of which is one of the only museums in Paris to stay open on Tuesdays. These two buildings play a sizable role in Philippe Soupault's Last Nights of Paris, which I just finished—Soupault describes the skeletal roof structure of the Grand Palais as a sinister landmark of his noctural ramblings. I am quite enamored of the doorway of the Petit Palais (below, and also the opening image of this post):

Quite peckish by this point, we ate at the café at the Petit Palais, which is a lovely outdoor courtyard with a lush little garden and kind of a colonial vibe.

We ended up staying to take in the current exhibit on Jean-Louis Forain, sometimes known as the youngest member of the Impressionist movement (he was nicknamed "Gavroche" by Manet and Degas, after the precocious urchin of Hugo's Les Misérables). Impressionism isn't usually my favorite movement, but Forain proved interesting for the variety of media in which he worked (oil and watercolor, but also ink, lithograph, and even a set of sketches transformed into tile mosaic), and for his bridging of eras and peer groups (friends with the above Impressionists, he also knew Verlaine and Rimbaud). His work is also interesting for its social conscience, which sometimes turned reactionary; the exhibit includes several of the antisemitic newspaper cartoons he drew during the Dreyfus Affair.

Forain's painted work ran the gamut from extremely gestural and full of movement, to quite polished, and although much of his material was similar to Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec (on whom he was an influence), his work seemed to me to be more concerned with social inequities. For example, he painted and drew many ballerinas, as Degas did, but many of Forain's pieces focus on the coercion involved when poverty-stricken dancers were put in a position of basically needing to accept the advances of wealthy but sleazy men in order to achieve a decent standard of living. He also did some gut-wrenching canvases of the carnage of WWI, where he served as a correspondent from the trenches. All in all, a fascinating exhibit! The Petit Palais was also showcasing the work of architect and interior/furniture designer Charlotte Perriand, but although her midcentury modern furniture looks gorgeous and right up our alley, the museum was closing by the time we finished with Forain, so we moved on.

It felt good to get walking again, which is nice because it was a longish walk to our next destination: 102 Boulevard Haussman, where Marcel Proust lived from 1907 to 1919. This is apparently the place where the famous madeleine was actually consumed. There's nothing really there now: it's a very busy, urban street, and the ground floor of Proust's former building now houses a bank. Still, the above shot could be the very window he attempted to avoid looking out of while locked up in his cork-lined bedroom writing. In actuality, having seen the degree to which his houses were right in the middle of the hustle and bustle of Paris life, I now think Proust was less crazy for the cork-lining and nocturnal hours than I did previously. I would go to great lengths to avoid distraction, too!

We ate dinner in kind of a sketchy Italian joint, which was at least relatively cheap for this semi-swanky area of Paris. (But seriously, the cook was a dour-faced Italian man with a facial scar. And we were the only people in the place. And the waiter hovered just outside the door, glaring at passers-by. The food was okay but it still felt like a mob front.) It was only a few blocks from another Proust destination, so we hastened over to 9 Boulveard Malesherbes (above), the site of the writer's childhood home. There is still (or again) a plaque there advertising a doctor's practice, which is fitting given that M. Proust père was himself a doctor. Being full of food and wine, possibly supplied by the Paris mafia, we stood a while and tried to envision the corner as it must have looked in the late 19th century, when little Marcel was growing up there. It's located in a little courtyard where five streets come together, and today the ground floor storefronts are occupied by a mix of French clothing shops, restaurants, and multi-nationals like Burberry.

Judging by the several people who left the building when we were standing there, and by the surrounding stores, I'd guess most of the occupants are middle- to upper-middle-class, which was pretty much the Proust family's situation as well. I'm not sure if it would have been equally commercial back then or not. The vrooming engines of cars and scooters would have been replaced by the clip-clop of horse hooves, and the dog poop on the streets would have been joined by horse dung. It's amazing to reconcile all the frenzy of these two neighborhoods with the organic-seeming flow of A la recherche du temps perdu.

On our way home we happened past the Gare St. Lazare (above), and I took a few photos before the guard swooped down upon us and notified us that photography c'est interdite. I have had this same experience in Washington DC, but apparently I don't learn. Either that, or my strong desire to photograph train stations overcomes my better judgment. As you can see, the sunset was lovely, and it just got lovelier as we made our way back to the flat and to bed.

Tomorrow is Wednesday, and most museums in Paris are open on Wednesdays. So we might have another try at the Cluny / Gallimard combo. Or something different! We'll let you know.

Cross-posted to Family Trunk Project.