Once, when I was enrolled in a Victorian Literature class in college, reading novel after essay after poem that grieved deeply over the religious upheaval brought on by the scientific breakthroughs of Charles Darwin and others, I asked my professor whether there weren't any 19th-century authors who felt liberated, rather than bereft, by these developments. As a profoundly a-religious person myself, I can try to imagine myself into the position of Arnold, Tennyson, Ruskin and others, who either grieved the loss of, or struggled to reconcile, their Christian beliefs with new geological and biological evidence. (Though I have trouble understanding the objection to a metaphorical reading of the Bible, which would seem to tie up all these problems with a neat little ribbon). But I would have thought that some 19th-century writers would embrace the demise of the god-concept and welcome a life of intellectual freedom and self-determination. My professor thought a while and then said yes, there were those writers, but that we wouldn't be reading Nietzsche in this class.

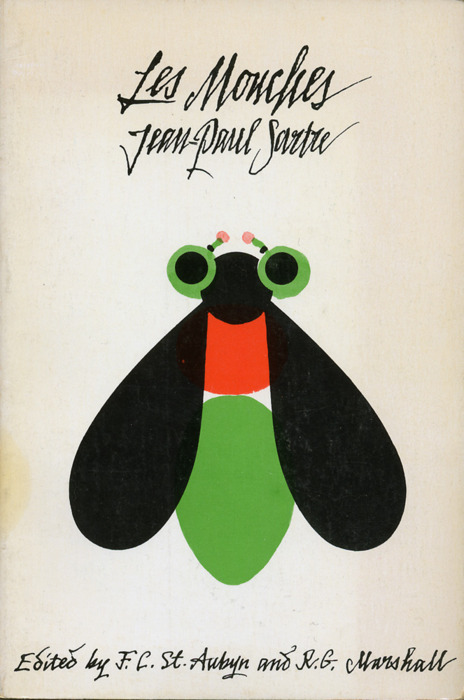

Nor have I read him since. But Jean-Paul Sartre's Les mouches (The Flies), an existentialist re-telling of the murder of Aegisthos and Clytemnestra at the hands of Orestes and Electra, comes close to what I was looking for back then, despite not having been written until 1943. Sartre takes the classical Greek tale, in which Orestes returns from his exile and is egged on by his long-lost sister Electra to avenge their father's death by killing their mother and her lover, and turns it into a parable about the changeable reality of gods in human lives, the role of remorse, and the power of free will. Having just read Anne Carson's translation of Sophocles's Orestes, the contrast was particularly clear in my mind between the crushing inevitability of the characters' fates in Sophocles, and the clarity with which Sartre's Orestes freely creates his own destiny.

There are other differences. In Sartre, we see the effects of Clytemnestra's and Aegisthos's crime on the regular citizens of Argos. The common people share in their rulers' guilt—something that feels alien to the royalty-centric worlds of Aeschylus, but very appropriate to a France of 1943, in which citizens had to decide whether to support the Resistance or collaborate with the fascist Vichy regime. Fifteen years before the play's action, Clytemnestra and Aegisthos murdered Agamemnon (Argos's king, Clytemnestra's husband), but were immediately seized with horrified remorse at their action. This remorse has taken over their lives and their style of ruling, becoming the ruling cult of Argos. As Electra tells her disguised brother,

[L]a reine se divertit à notre jeu national: le jeu des confessions publiques. Ici, chacun crie ses péchés à la face de tous; et il n'est pas rare, aux jours feriés, de voir quelque commerçant, après avoir baissé le rideau de fer de sa boutique, se traîner sur les genoux dans les rues, frottant ses cheveux de poussière et hurlant qu'il est un assassin, un adultère ou un prévaricateur. Mais les gens d'Argos commencent à se blaser: chacun connaît par coeur les crimes des autres; ceux de la reine en particulier n'amusent plus personne, ce sont des crimes officiels, des crimes de fondation, pour ainsi dire. Je te laisse à penser sa joie lorsqu'elle t'a vu, tout jeune, tout neuf, ignorant jusqu'à son nom: quelle occasion exceptionelle! Il lui semble qu'elle se confesse pour la première fois.

The queen is just amusing herself at our national game: the game of public confessions. Here, everyone shouts their sins in each others' faces; and it's not rare, on feast days, to see some merchant, having closed up shop, crawling on his knees through the streets, rubbing dirt into his hair and yelling that he's an assassin, an adulterer, or a liar. But the people of Argos are starting to get bored. Everyone knows everyone else's crimes by heart; the crimes of the queen, in particular, no longer interest anyone, they're official crimes, founding crimes so to speak. I'll leave you to imagine her joy when she saw you, young and new, not even knowing her name: what an extraordinary opportunity! It feels to her like she's confessing for the first time.

Thus the guilt and penitence of Aegisthos and Clytemnestra have become the dominant characteristic of the entire society—everyone is defined by their misdeeds, and are forever trying to leech some kind of absolution out of everyone else—a vicious spiral that becomes more and more insular and stagnant as time goes on, as symbolized by the plagues of flies that infest the city. The big national fête, for example, involves twenty-four hours of heightened fear and remorse for the citizens of Argos, as a priest moves a boulder away from a cave entrance, and Aegisthos declares that the city's dead have returned from the underworld. (Whether or not the dead actually have returned is a point of contention among the citizens, highlighted by a darkly funny conversation between two guards about whether the dead flies return on this night, or only the dead humans.) Jupiter, god of flies, death, and decay, rules over Argos, feeding on the back-looking contrition of its citizens, and he often demonstrates his vested interest in keeping the Argos people enchained.

Into this pit of recreational remorse steps Orestes, reared in privilege away from Argos and only recently informed of his parentage. Until now he has had no real ties, wandering the world at liberty, belonging to no one and with no one belonging to him. The central conflict of the play, then, involves Orestes's inner struggle over how to claim ownership over his ancestral past, not having shared his sister's years of servitude and hatred, and whether he can or should act to break the cycle of fear and remorse in Argos. In Sartre's hands his eventual murder of Clytemnestra and Aegisthos becomes a declaration of independence, a unique, freely-chosen action, over which Orestes takes full ownership and for which he refuses all regret. The furies, who in classical Greek tragedy haunt Orestes to madness after he murders his mother, are here sent by Jupiter as partisan beings who attempt to bully him into remorse—and must fall back when they see that he does not fear them, or regret his action.

It's such an interesting take on the story, because if I were to choose any era of literature that inclined least toward an expression of free will, I would probably choose ancient Greek tragedy. In a way, Sartre himself accomplishes something similar to Orestes's coup in overthrowing the dominant worldview in Argos: just like the people of Argos have believed for years that they are defined by the confession of their sins, the tellers of this story have always believed that the events therein were fore-ordained and controlled by the gods. For Sartre, however, as Jupiter unwillingly admits,

Quand une fois la liberté a explosé dans une âme d'homme, les Dieux ne peuvent plus rien contre cet homme-là. Car c'est une affaire d'hommes, et c'est aux autres hommes—à eux seuls—qu'il appartient de le laisser courir ou de l'étrangler.

When once freedom has burst into the soul of a man, the Gods have no power to act against him. Because he's now a human affair, and it's up to other men—to them alone—to let him run or to strangle him.

I've hardly mentioned Electra at all here, but Sartre's depiction of her was another unique feature of Les mouches, and the only part of this play that was a bit disappointing to me. In Sophocles and Euripedes (I haven't read Aeschylus's version of events after Agamemnon's death), Electra is if anything the stronger, more vengeful, more obsessive sibling, the one who never falters in her quest to see her mother dead and her father avenged. She is the one who cares for Orestes after the murders are done, the one less affected by the furies. In Sartre this dynamic is reversed: although Electra initially desires Orestes to kill Clytemnestra and Aegisthos, she recoils when faced with the reality of the deed. In the end she can't resist the pull of the remorse-cult on which she was raised, fleeing back into the killing arms of Jupiter. It's an effective choice, I think, and I understand why Sartre worked in this contrast between brother and sister, but I was still a tad bit disappointed not to encounter the blazing, defiant Electra I have come to expect.

All in all, though, another fascinating foray into existential theater, and a rare opportunity to see enacted a celebration of human self-determination, even when that self-determination is difficult and morally ambiguous.