It's hard to believe that we've arrived at the morning of our last full day in Paris! I was so exhausted last night that I didn't have a blog post in me; luckily we're taking it easy this morning and enjoying the light breeze and the view from our flat, so I can put together a post about our yesterday's adventures.

We started out with a little literary tourism in the first arrondissement, locating the site of the apartment at 9 Rue de Beaujolais in which Colette lived from 1938 until her death in 1954. This is the first of these little bookish pilgrimages whose site actually seems to fit—even to evoke—the writer in question; the flats are built over a short gallery with music box and doll shops, and on the back gives onto a public garden, which Colette would, of course, have loved. The streets surrounding the building are narrow and twisting, and discourage any quantity of car traffic. I can easily imagine Colette living out the final decades of her long life here, with her young lovers and her cats.

From Colette's flat we strolled over to the wide Boulevard des Capucines and Le Grand Hôtel. These were the deluxe accommodations of the nineteenth century, and I'm sure many luminaries have lodged there (Edith Wharton, perhaps?), but the one we had in mind is Oscar Wilde. This is the hotel in which he was staying when he dashed off Salomé on a whim, after a vigorous luncheon party. Apparently, in one of several anecdotes that convince me I would have found Wilde obnoxious in life even if I'm somewhat charmed by reading about his antics, he dashed down to the street below his window, where a gypsy orchestra was playing. He accosted the band leader, and pronounced "I am writing a play about a woman dancing with her bare feet in the blood of a man she has craved for and slain. I want to you play something in harmony with my thoughts." Oh, Oscar. The hotel building takes up the whole triangular block, and is still very posh; one night there costs about what we spent on a whole week in our Montmartre flat.

From Wilde's hotel, we turned our steps at last toward the Louvre. I don't think I've ever done so much preparation for a museum visit: my idea, knowing that Proust spent many hours in the Louvre, was to research which of the works referred to in A la recherche du temps perdu are there, and to put together a tour based on those. In addition to being interesting because of my love of the book, this plan had the benefit of providing an "angle" from which to attack the behemoth of a museum, which would have seemed totally overwhelming if I'd approached it cold. It ended up being very rewarding; the only downside was that we spent a bit more time in 18th-century French painting than we might otherwise have done—but even in that case, it was interesting to learn about an era I wouldn't have gravitated to on my own.

[My grandmother] would have liked me to have in my room photographs of ancient buildings or of beautiful places. But in the moment of buying them, and for all that the subject of the picture had an aesthetic value, she would find that vulgarity and utility had too prominent a part in them, through the mechanical nature of their reproduction by photography. She attempted a subterfuge, if not to eliminate altogether this commercial banality, at least to minimise it, to supplant it to a certain extent with what was art still, to introduce, as it were, several "thicknesses" of art: instead of photographs of Chartres Cathedral, of the Fountains of Saint-Cloud, or of Vesuvius, she would inquire of Swann whether some great painter had not depicted them, and preferred to give me photographs of 'Chartres Cathedral' after Corot, of the 'Fountains of Saint-Cloud' after Hubert Robert, and of 'Vesuvius' after Turner, which were a stage higher in the scale of art.

Putting aside Marcel's grandmother's dismissal of photography as art, I love the idea of "thicknesses of art," articulated here, and it occurred to me that this is more or less what we, and everyone snapping pictures in these museums, are creating. In remixing, re-cropping, shooting from an unexpected angle, or merely recording an image for note-taking purposes, we create another layer, another "thickness." Rooms that are very painting-heavy are generally less exciting to photograph, in my opinion, than collections with a wider variety of media, but this quote inspired me to try. For Marcel's grandmother the painting was merely a means of making Chartres Cathedral present in her grandson's room, but I was drawn to the leisurely-seeming people in the foreground, passing a few minutes on either side of the lane leading to the church in leaning against or sitting on the stone walls.

One thing I realized in preparing for this project, is how infrequently Proust's visual art references are to a specific painting rather than a general tendency in a painter's work. He'll say, for example:

[T]he moonlight, copying the art of Hubert Robert, scattered its broken staircases of white marble, its fountains, its iron gates temptingly ajar. Its beams had swept away the telegraph office. All that was left of it was a column, half shattered but preserving the beauty of a ruin which endures for all time.

which could refer to any of Robert's paintings of ruins (and he made a lot of them, the one above being one of my favorites we saw). Or, in another example, he might write that

The name Gilberte passed close by me [...] forming, on its celestial passage through the midst of the children and their nursemaids, a little cloud, delicately coloured, resembling one of those clouds that, billowing over a Poussin landscape, reflect minutely, like a cloud in the opera teeming with chariots and horses, some apparition of the life of the gods...

I think the Poussin clouds below are a very nice match here, but I'm sure there are others as well.

There were likewise many examples of the broken-hearted Botticelli virgins and Venuses to which Swann often likens Odette. The most affecting, in my opinion, were those in a room of frescoes actually relocated from Marcel's beloved Florence.

Of course, the most satisfying instances of an exercise like this is when Proust mentions a specific work which we could then search out. This happened a few times: Rembrandt's Bathsheba, for example, or this Luini fresco of the adoration of the Magi:

I should have wished [my parents] to understand what an inestimable present I had just received and, to show their gratitude to that generous and courteous Swann who had offered it to me, or to them rather, without seeming any more conscious of its value than the charming Mage with the arched nose and fair hair in Luini's fresco, to whom, it was said, Swann had at one time been thought to bear a striking resemblance.

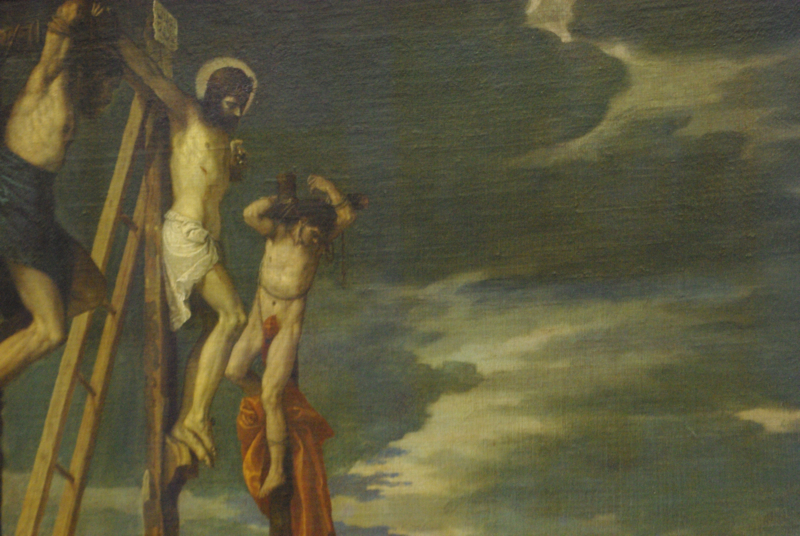

I was especially excited to find Veronese's Crucifixion painting, as it figures in one of my favorite Proustian passages, both for the beauty of its prose and for the hilariousness of Marcel's ridiculously overwrought psychology. And indeed, the skies depicted do have a certain modern, Parisian, and ominously massing quality about them.

Unhappily those marvellous places, railway stations, from which one sets out for a remote destination, are tragic places also, for if in them the miracle is accomplished whereby scenes which hitherto have had no existence save in our minds are about to become the scenes among which we shall be living, for that very reason we must, as we emerge from the waiting room, abandon any thought of presently finding ourselves once more in the familiar room which but a moment ago still housed us. We must lay aside all hope of going home to sleep in our own bed, once we have decided to penetrate into the pestiferous cavern to which we gain access to the mystery, into one of those vast glass-roofed sheds, like that of Saint-Lazare into which I went to find the train for Balbec, and which extended over the eviscerated city one of those bleak and boundless skies, heavy with an accumulation of dramatic menace, like certain skies painted with an almost Parisian modernity by Mantegna or Veronese, beneath which only some terrible and solemn act could be in progress, such as a departure by train or the erection of the Cross.

This is especially cool since we, too, are about to depart for "Balbec" (actually Cabourg) on the Norman coast; luckily for us, however, we shall not be departing by train.

Of course, in looking around for Proustian references we discovered other works that were interesting and appealing. Because my primary interest is modern and contemporary art, I tend to gravitate toward things that remind me of later artists. The backdrop of the above painting, for example, reminds me strongly of De Chirico's flattened, shadowy street scenes, and the Commedia dell'arte figures are reminiscent of his surrealism as well. I tend to love sketches and unfinished pieces as well; this study by Ingres for a later, work struck me as particularly modern.

As a lover of modern art, I was also inspired by the extent to which the curators of the Louvre choose to intermingle old and new—not in the actual collections, which stop short of Impressionism, but in the building itself. The most famous example is, of course, I.M. Pei's steel and glass pyramid entrance hall, located in the grand courtyard formed by the three wings of the French Renaissance palace. But there are other examples as well: in a gilt room housing Greek and Roman antiquities, the ceiling is a giant painting by American contemporary artist Cy Twombly.

Likewise, on a series of grand staircases in the Richelieu wing, French contemporary artist François Morellet (he of the square paintings of yesterday) has designed a series of very cool leaded-glass windows designed to look as if an entire pane is off-kilter:

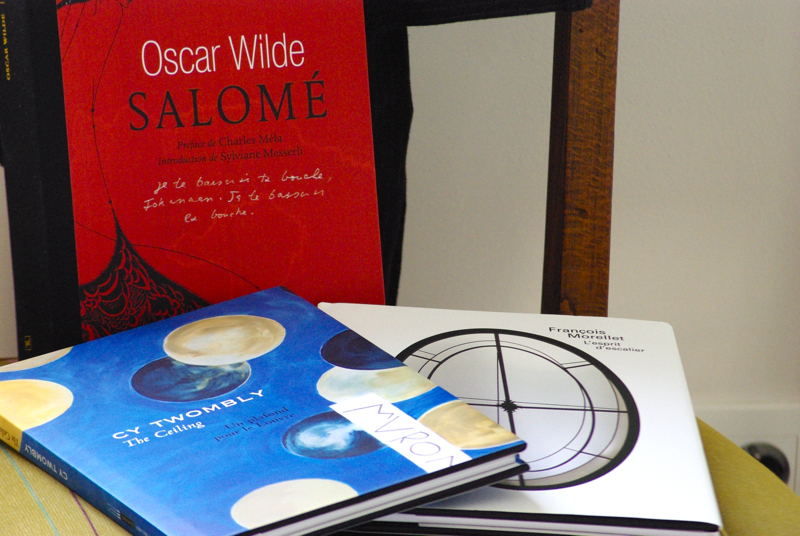

Finding myself very much drawn to these contemporary details, I was excited to find that monographs were available on both the Twombly and Morellet projects. My third bookshop find, amazingly appropriate given the Wildean accents of the day, is a gorgeous presentation of Salomé in three sections: after a scholarly introduction, a facsimile of the original hand-written notebook in which Wilde composed the play; then the first French edition; and finally, the first English edition, translated by Lord Alfred Douglas and illustrated by Aubrey Beardsley.

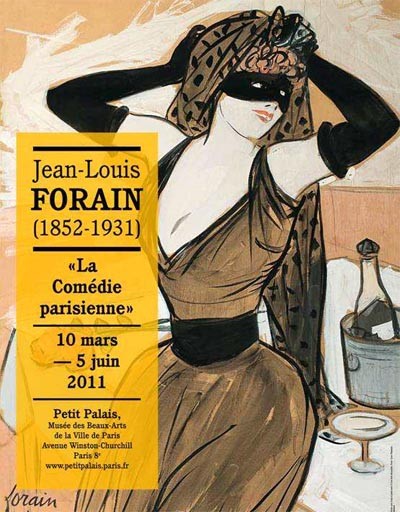

We exited the museum to one of the most gorgeous sunsets I've ever seen, and made our tired way home. This last afternoon we're off to see the Opéra de quat'sous (Threepenny Opera) at the Comédie Française. A bientôt!