Yet again I have an overwhelming amount to tell you about a two-day period! We left our relaxing mini-castle and vineyard yesterday morning and made our way out to the Dordogne countryside, walking in the footsteps of the Romantic poets who first confused the estate's owners by insisting on making a pilgrimage to the former home of Michel de Montaigne, pioneer of the essay form.

These days it's set up a bit more like a tourist attraction than it was back in the late 18th century, although not much more. There was only one other car in the small parking lot when we arrived, and a group of friendly British and Welsh students greeted us and led us along the path through the grounds (modest by the standards of a Renaissance château, but still quite lovely), and to the tower itself. The tower is the only part of the château that remains of the house that Montaigne himself knew, the rest having burned down and been replaced by another house, which is still privately owned. But the tower would have been the most interesting part anyway, since that's where Montaigne went to get away from his forceful wife and mother, to sleep, and, of course, to write.

Here there is the opposite problem we found at Mont St. Michel: today this site is peaceful and quiet, and Montaigne biographer Sarah Bakewell points out that in this environment it's easy to imagine Montaigne as a retiring man, lost in his meditations. In fact, during his lifetime this was a working farm, and would have been teeming with all kinds of human and animal life, including yelling, mooing, cackling, and all the coming and going inherent in farm life. As one gesture toward all the agricultural activity that took place here, Montaigne's saddles are on display in his study; it's possible that one of these was involved in the near-fatal riding accident that changed Montaigne's worldview and enabled him to become more accepting of the idea of his own death. I particularly thought of my friend Ariel when I saw these, as we first read Montaigne in a college seminar together and, being a horsewoman, she would probably be able to make more of a saddle than I can. Hi Ariel!

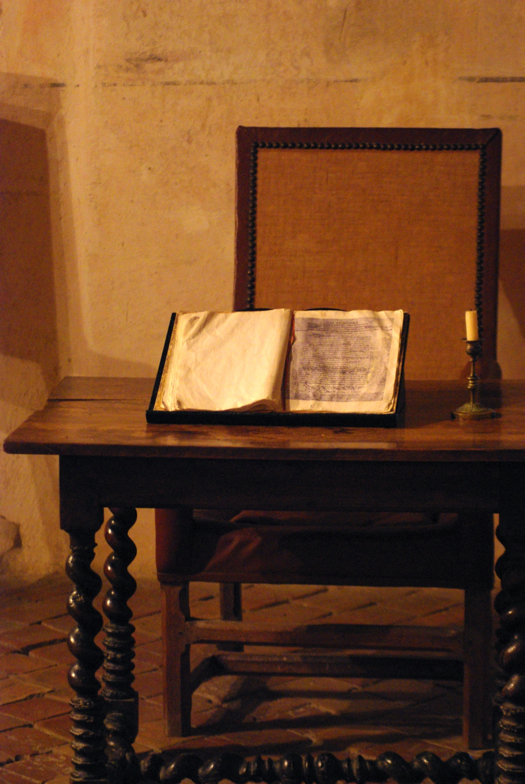

One striking thing about the rooms in the tower is that by modern standards they are very small: David (5'11") had to duck to get through the doorways, and even I (5'4") was aware of them when passing through. The tower was Montaigne's sanctuary in more than one sense, as the ground floor contains a small chapel where he heard mass, which is still painted with the coats of arms and trompe l'oeil niches and columns that he had painted there. Up a very worn, steep stone spiral staircase is his bedroom, equipped with an extra niche next to the bed (for getting warm in the winter in an era of un-glazed windows) and an audio channel that was installed from the chapel to the bedroom, to enable the aging, bedridden Montaigne to listen to masses. Up another set of spiral stairs is the study, with its rafters engraved with sayings in Latin and Greek. Certain sections of the carvings are facing one way, while others are facing the opposite; this allowed Montaigne to pace back and forth, reading all the while.

During his lifetime all of his then-impressive collection of books would have lived up here too, but they were sold off after his death and visitors have to imagine how much more full and cozy the little room might have seemed with a thousand volumes shelved on the wall across from the writing desk.

The Montaigne estate was, and is again, covered with vineyards (although in the interim they were torn out), and we grabbed a bottle of their wine on the way out. In addition, of course, to a volume of the Essais. The friendly Welsh and British ladies waved us on our way and we were off on the longish drive to Toulouse, to meet up with our friends Yves and Marie Christine. After a few misadventures with getting turned around on the freeway and having to go through a ridiculous number of toll plazas as a result, we arrived and were fed an excellent salade niçoise before heading to Les Abbatoirs, a former slaughterhouse subsequently converted into a modern art museum.

A big star of the museum's collection is the curtain that Pablo Picasso designed for the first July 14 celebrations after the triumph of the Front Populaire in 1936 (which established things like paid vacation and workers' rights in France). The above is just a detail of it; the thing is of an epic size, a full two floors tall, and can be viewed from three different levels of the museum. They really make the most of their light, open, many-leveled building to show this piece to best advantage. Marie Christine and I were interested to learn that it was scaled up from a smaller drawing using the same grid-line technique that she uses to design tapestries, and I use to design knitting charts!

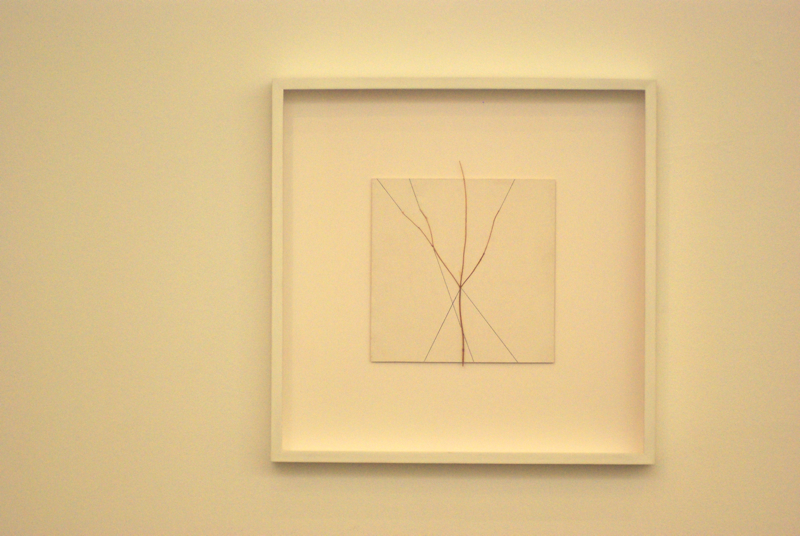

I was excited to see a few more pieces by François Morellet, the artist responsible for the "Esprit de l'escalier" windows at the Louvre, which I wrote about a few entries back. In the two pieces at Les Abbatoirs, one large and one quite small, he plays with the juxtaposition between the organic lines of found natural objects, and the exact geometrical lines created by humans. I liked both pieces and I liked their placement in relation to one another, on either side of a doorway: this delicate piece was offset by its much larger cousin, also in blacks and whites but made of a giant branch and black acrylic tape.

A new discovery for me was Yolande Fièvre, who makes these amazingly appealing, densely-packed box constructions out of found objects. Those who know my taste in visual art will know that "box construction" is pretty much my favorite ever medium (Joseph Cornell being one of my favorite visual artists), and Fièvre's work is right up my alley: textural and evocative, but much denser than Cornell's. As suggested by the title of this one, each of her pieces is like a whole city in miniature, and as I stood and gazed at them, more and more details jumped out at me: objects arranged into the shapes of human figures; the texture of wheels and axles underlying the surface; textural waves leading the eye from one part of the piece to another. You can check out images of a few more of her pieces here; I'd love to pick up a monograph, but they don't seem to be readily available. A little research does indicate that Fièvre was friends with Raymond Queneau and André Breton, though, which only makes me more intrigued to get to know her art!

In an extremely odd coincidence, right after posting twice about the Bayeux Tapestry, which details the events leading up to and including the Battle of Hastings in 1066, I ran into another, very different representation of that same battle, this one by abstract expressionist Georges Mathieu. Crazy! The two depictions are about as far apart as you can get, but I think they both manage to convey the intensity, energy and chaos of battle. And they are both, somehow, contained as well: the Bayeux Tapestry is very long but very small top-to-bottom, and its narrative was constructed to justify the way events turned out. Mathieu's canvas is explosive and chaotic, but the chaos is all neatly contained within the borders of the black background; none of the lines threaten to overflow the boundaries of the painting.

After leaving the museum's interior we took a walk around the grounds, which continue to make good use of the preexisting architecture; in the brick niches on the outside of the building are a series of ten or more mosaics by Fernand Léger, which I quite liked. The gardens next to the museum are home to an amazing steampunk carousel, which Marie Christine tells us was a project designed to employ out-of-work artists while also creating something TOTALLY RAD (okay, that last was my editorializing). Surely the most stylish carousel I've ever seen, it features Jules Verne-style flying machines, a giant clockwork ant, an ancient-looking turtle, an ironclad rhinoceros, and the riveted fish above, among many others.

Marie Christine then took us for a lovely walk along the promenade that borders the river Garonne, which runs through the center of Toulouse. I always prefer my cities to have a river running through them, so this helped me warm up to Toulouse right away. It actually reminds me a bit of Portland, with its large student population and its riverside esplanades, full of people lounging on the grass taking advantage of the nice weather. One obvious difference, though, is the amount of history here and the cultural memory of times long ago. Crossing the bridge, for example, Marie Christine pointed back to an area by the bank and informed us that that's where people used to be locked in a cage and dunked repeatedly in the river until they divulged whatever information they were being "interrogated" about. And further on, a niche by the door of a former hospital building was revealed to be the revolving platform where distressed parents could deposit infants they were abandoning. You can see it to the right of the main door in the picture below:

And so after a bus ride and a delicious dinner (including cheese AND dessert courses, and a conversation about how the French are opposed to the very idea of drinking water instead of wine with cheese or sweets), we had a macaron-making lesson (on which more later) and headed to bed.

Although he was born in Lyon, the writer and early aviator Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (of Le Petit Prince fame) spent time in Toulouse, and the city seems to have adopted him wholeheartedly as a native son. A major street is named for him (with another one named after the Little Prince), and murals and statues abound. The above is a detail of a mural near our house, and below is a statue in a charming setting, next to a duck pond crossed by a footbridge in the Royal Garden. I like how the author and his character seem to be in conversation.

In other Saint-Exupéry news, we paid a brief visit to the Hotel Grand Balcon, where the author and other pioneers of aviation would gather, drink, and also sleep, in their glory days of the late 1920s and 1930s. The vintage mosaic floor tiles are still intact, although the interior has been remodeled into an ultra-chic black-and-white cocktail bar and restaurant.

Marie Christine is a wonderful guide around the city, and imparted lots of information about Toulousian history. A wealthy city during the Renaissance due to its specialty as an exporter of woad (the plant used to create the blue and green dyes for the Bayeux Tapestry, and apparently intensely stinky to process into a dye), the town fell on hard times with the importation of indigo and didn't fully recover until the aviation/space industry came here in the 20th century. There are still lots of beautiful Renaissance details, especially when you are with Marie Christine, who knows where to look. David and I both loved the gargoyle scratching his ear on the windowsill above, and the carvings below are found in the courtyard of an erstwhile inn, Le Vieux Raisin, which has now been converted into doctors' and lawyers' offices. Facing this young man and woman are their elderly counterparts, their twisting lower halves replaced with bundled sheaves of grain.

We were introduced to several aspects of typical Toulousian architecture, including these cool "antefixe" roof tiles, which are affixed to the outside edge of the roofs (originally to hide the chimney apparatus). Some, like these with little faces and fleurs-de-lis, are quite elaborate.

Toulouse is also full of gardens and green spaces—another similarity with Portland, although the latter's gardens are of course not surrounded by the remnants of the medieval city gates...

...nor do they feature quite this shade of hydrangea (this is right out of the camera, with no manipulation). At least, if they do, I haven't seen them.

Today we're headed back into town for further adventures. A big thanks to Yves and Marie Christine for their hospitality in putting us up and showing us around their lovely town.