We had a lovely last day in Paris. (But not in France; we're here for two more weeks!) After a leisurely morning in, we headed back to the neighborhood of the Louvre to a performance of Opéra de quat'sous (Threepenny Opera), with music by Kurt Weill and book by Bertolt Brecht. Neither of us have ever seen a production of Threepenny Opera, but I have long adored the music in both English and German (I own three recordings of it), and in college I studied John Gay's 1728 Beggar's Opera, which was the source material for Brecht's story. So it was a super-exciting opportunity to see it staged by such a prestigious company. And it was also pretty much the perfect piece to see in French, since I was already very familiar with the characters, the music, and the storyline, so it wasn't that important that I could only understand about 10-15% of the words spoken. (David had neither so high a familiarity nor such a high percentage of language comprehension, but he was a very good sport. And he likes the music too.)

Despite what unqualified judges we are, I thought it was a great performance. The staging and set design was fantastic—the director modernized the action, setting it in post-Thatcher London, and the scene changes were incorporated into the action in interesting ways. For example, in the change leading up to Macheath and Polly's "wedding," Macheath's thugs are supposed to be setting up the nuptial feast using furniture and dishes from their plundered store—in this production they simply move the set pieces into place at the same time. It worked very well. Acting highlights definitely included Véronique Vella as Celia Peachum (a brilliant physical comedienne, probably under five feet tall and played Mrs. Peachum as a whirlwind of manipulative yet no-nonsense theatricality), and Thierry Hancisse as Macheath (charismatic and sleazy in just the right measure—I love the idea of Raul Julia in this role but I honestly think he would have been too far on the charming/sexy side).

There is apparently, although I don't know the details, a debate about whether Mackie's new bride Polly or his old flame Jenny should sing "Pirate Jenny," and this production gave it to Polly. This has always struck me as a strange choice; for one thing, if Jenny sings the song, which after all does bear her name, we get a greater insight into her anger and ambivalence earlier in the play. If she doesn't sing it we don't even see her until halfway through, which is odd for such a pivotal character. Still, Sylvia Bergé did a good job at getting across the weight of the character even with such a late introduction, and that would probably be even truer if I had understood her words better. She and Hancisse traded off verses and stood front and center during the first finale ("What keeps mankind alive?"), which reinforced the importance of both her character and the bond between them. I've heard and read versions of the story which paint Jenny as more or less in love or in hate with Macheath; from what I could tell this production veered toward the hate side, although Bergé's Jenny was still obviously conflicted about turning in her former pimp and associate to the hangman. The "Ballad of Immoral Earnings" piece, for example, was staged in such a way that her more vicious lyrics seemed sincere, whereas her more nostalgic lyrics seemed like manipulation of Macheath. In any case, it was super exciting to see this play staged so well, and I've been walking around humming "Mack the Knife" for the rest of the day.

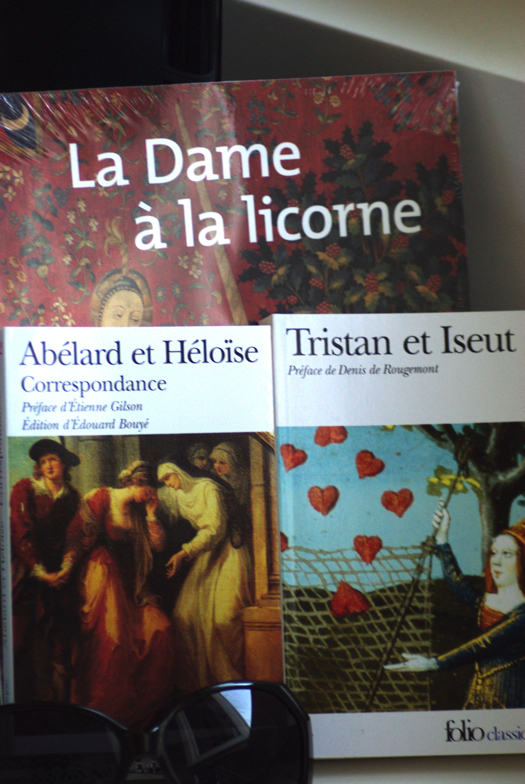

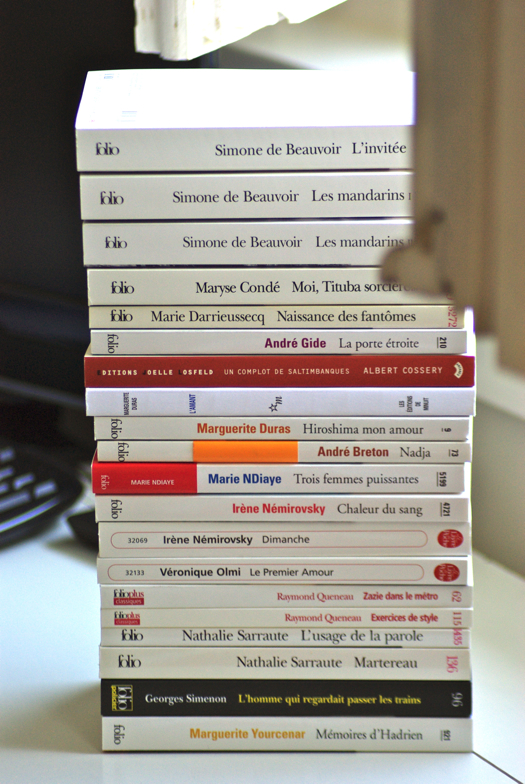

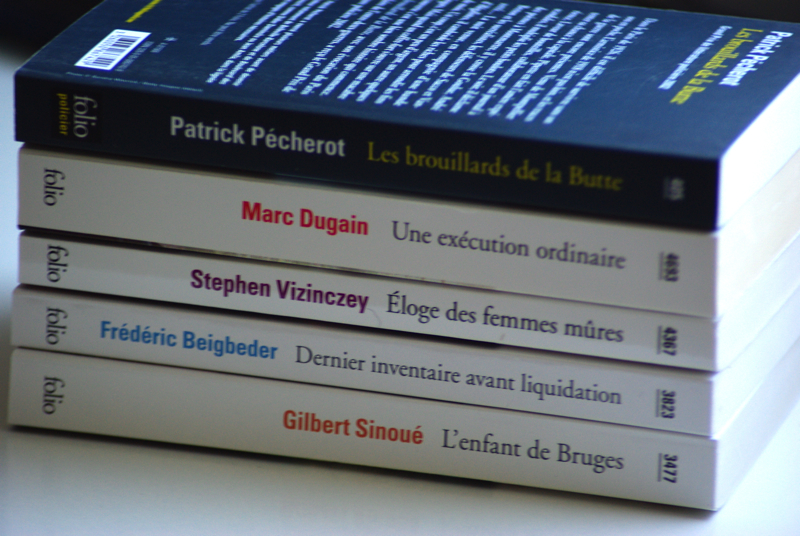

After the play we strolled down to the Seine and across the pedestrian Pont des Arts, then briefly along the quai famously lined with bouquinistes (bookstalls). Having just re-packed my suitcase and being slightly nervous about my ability to lift its new-found bulk, I did not actually buy anything, but it was fun to browse a bit. Especially in the stalls that chose to forgo the postcards of John Lennon in his New York tee shirt and Jim Morrison with his beaded necklace, in order to stock actual books.

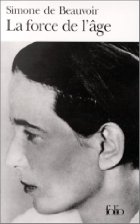

As I was starving, we stopped for a snack at Café Flore, Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre's home base during the 1930s. They would often sit here working and socializing from morning until night—Beauvoir particularly, during the war years when her own home wasn't heated due to shortages. These days it's pretty touristy, but you can still discern some of the old ambiance in the tiled floors, the narrow, worn wooden spiral staircase up to the second floor, and the few jovial customers on speaking and back-slapping terms with the waitstaff.

After soaking up the history for a while, and very much enjoying the small terrier/dachshund mix that came in with a man at the table next to us, we ducked across the way and picked up a little box of macarons at famous bakery Ladurée. Our friend Marie Christine has agreed to make macarons with us when we're staying with her and her husband Yves in Toulouse next week, so...just consider this research. We stood in line in the tiny shop to order a flavor selection including chocolate, rose petal, orange flower water, pistachio, violet and raspberry—but unfortunately, the strawberry-mint flavor so touted by the window display had already run out for the day.

Determined to go out for a proper dinner and to do it at a European hour, we wandered around for a bit, ducking in to the church of St. Germain des Près for the end of an evening mass, which was lovely. Not wanting to disturb the service itself, we sat in a nave to the side of the main aisle, gazing at a smallish painting which we later realized was a Fra Angelico. St. Germain des Près is one of David's favorite spots from his one previous trip to Paris, so we were both glad to return there together.

More wandering, and we happened by the hotel where, in 1900, Oscar Wilde met his rather gruesome end. Coincidentally, or maybe not, it turns out that Borges also stayed there quite a bit in the 1970s and 80s.

Finally, having succeeded in waiting until after 9pm to seek out our restaurant, we felt justified in turning our steps toward Fish La Boissonnerie, a tiny but totally charming restaurant that had been recommended to us. It really was delicious; David had the rabbit and I had a salmon steak, with a shared carafe of amazing Chinon cabernet franc and followed by a crème brûlée flavored with verveine. The wine was so good that we decided to buy a bottle to take home with us; apparently the delicious repast made us temporarily forget the weightiness of our suitcases. Tomorrow on the métro to pick up our rental car, we may be cursing all our purchasing of heavy objects. At least David's tea habit is lighter on the muscles than my penchant for books and wine!

Tomorrow we're off to the Norman coast followed by the Loire valley. I'm not 100% sure what internet connectivity will be like in our future locations, so the blog entries may become more sporadic. I'll be sure to check in when I can, though, and am very much looking forward to the next segment of our trip.

Cross-posted to Family Trunk Project.