I've been following Tom's Portuguese Literature Challenge reading lists over at Wuthering Expectations—and as a result my eye, on the lookout for things to do on a holiday weekend in Seattle, was caught by the description of Raul Ruiz's Mysteries of Lisbon. Adapted from a novel by the extremely prolific but barely translated 19th-century Portuguese novelist Camilio Castelo Branco, this nearly five-hour film seems at first glance a standard costume drama, albeit with rather more stunning cinematography. (Really stunning. Seriously.) As it turned out, though, Mysteries of Lisbon is more interesting than that.

Not in terms of plot. Any of the actual plot points here would be familiar to readers of Dickens, Collins, Brontë, or any other craftsman of Victorian-style melodrama. You've got your orphans, your rakes, your naive maidens, your hushed-up scandals, your duels and battles, your lovers expiring tragically in each others' arms, your picturesque descents into madness, your judiciously-placed revelations of previously-unsuspected parentage...you know the drill. What distinguishes Mysteries of Lisbon is its structure: rather than a narrative in which a multitude of disparate threads eventually come together into a neat conclusion, Lisbon presents a forking, open-ended structure in which each character's narration leads to the narration of another character. And while the details of each narrator's life do relate to and sometimes explain the details of others, each section raises at least as many new questions—and new avenues for potential in-depth exploration—as it resolves.

A concrete example: we begin the story with narration by young João, an orphan and ward of a provincial Catholic school, who is consumed by curiosity about his unknown parents. As he learns more about his origins, we're introduced to his mother, Angela de Lima, and the priest who runs the school, Father Dinis. The film branches away from João as Angela narrates the story of her life with her brutish husband; then branches again as Father Dinis narrates the story of how he met João's father; then branches yet farther as we get narration from João's father's point of view. In the course of all these stories we are introduced to further characters who later become narrators or primary players in another character's narration: Angela's count husband has a narrative section, as do Father Dinis, charismatic semi-pirate Alberto de Magalhães (played superbly by Ricardo Pereira), a Parisian ex-lover of Magalhães's, the elderly priest Father Dinis meets when attending the count's deathbed, and so on. With each branch of the story we encounter more details and secondary characters whom we suspect might become central in a future section; some of them do, while others remain cyphers. I imagine that one reason for the film's five-hour running time is simply to demonstrate the potential infinitude of this method of storytelling: there's no narrative reason it could not continue on, branching here and there, indefinitely.

Despite the film's unusual narrative technique, I don't want to imply that the viewer is left with a huge number of significant questions at the end of five hours. However, there are quite a few tantalizing suggestions that gesture at the open-endedness of the world presented here. Along with that open-endedness, I think, goes a certain faint whiff of the bizarre or grotesque: the film featured the occasional surreal detail (Magalhães's oddly mincing footman, for example, or the pacing background figure in the duel scene) presented without any explanation whatsoever, in a way that reminded me of David Lynch's Twin Peaks. It would take multiple viewings to track properly all the questions answered, let alone all that are asked, but here's what I was left wondering about, or interested in paying attention to on a re-watch:

- Father Dinis and his relationship with his "sister"; we never get the back-story here, and it's one of the most intriguing teases of the film. Possibly, we could deduce more based on early clues.

- Who is the kid walking back and forth in the background of the dueling scene, who then shoots himself after everyone leaves? There might actually be evidence of this in the film, but if so I totally missed it. It's a great example of Ruiz's use of the subtly bizarre, though.

- What's with all the characters falling over and having fits? Is João/Pedro epileptic? Is Father Dinis's father epileptic? Is there some kind of implied heredity there? Or is everyone just prone to swooning?

- Two back-stories we're explicitly denied concern the relationships of Eugenia—why doesn't she accept the money left to her by her lover, and how does she then end up married to Magalhães? We hear that she wants to tell Father Dinis her story, and we see the priest sitting at her table right after (presumably) having heard the story, but we never hear the story ourselves. This is the kind of trick Mysteries of Lisbon loves to play.

- Magalhães's semi-abusive relationship with his prance-y, occasionally violent manservant: delightfully weird, and never explained beyond Eugenia's offhand comment that the servant is "ill."

- There's a hilarious and affecting recurring motif of people (often servants) observing others through doors, windows, and other apertures. In one scene, for example, adulterous lovers who have just been found out by the woman's husband ask each other in consternation, "But how could he know? We were so careful!" Meanwhile, servants are watching them through at least two unbolted and un-sashed windows, creating an effect that's both funny and slightly sinister. In several other scenes, lovers woo while a third person looks on, raising the question of how the observer affects the scene unfolding, whether the lovers know they are being observed or not.

I'm so glad I got the chance to see Mysteries of Lisbon on the big screen, and it's the kind of film I hope to see released in some kind of Criterion Collection or special boxed DVD. Given that Branca's homonymous novel isn't yet translated into English, what I would most hope for from such a set would be clues about how much of the film's technique is taken from the novel—and how many of its lingering questions.

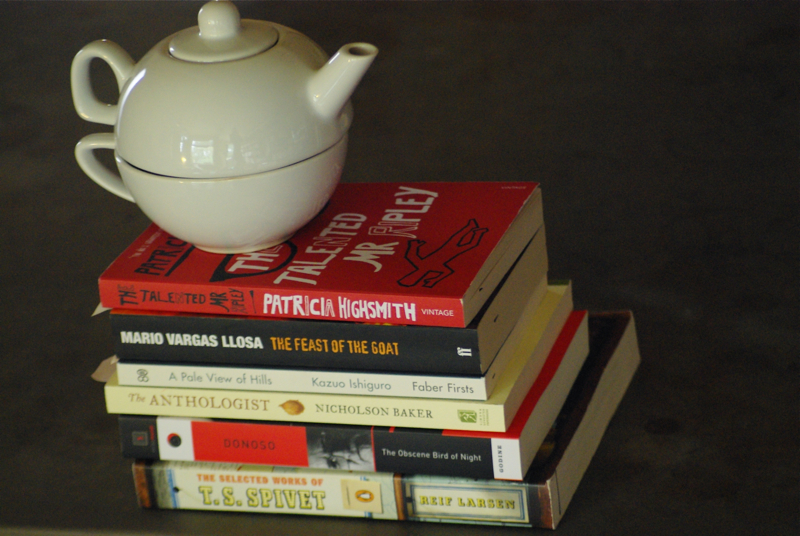

Oh yes, and I picked up a few books in Seattle, as well! I was going to avoid Elliott Bay Books in an effort to save money and space, but when it turned out that David was generously treating for food and lodging on this little trip (thanks, Sweetie!), and when, in addition, Lena pointed out on Twitter that the shop features bargain tables, and when, on top of all that, we ended up enjoying a delicious meal and wine next door at the Tin Table...well, enough of the excuses. Here's the loot. Except the Donoso these were each only five dollars, so I don't feel too decadent.

From the bottom up:

- The Selected Works of T.S. Spivet by Reif Larsen is the farthest I've diverged from my "comfort zone" in quite some time, as it was marketed as a Young Adult novel and garnered mixed reviews on release. However, the multimedia, non-linear presentation and the low price of $5 were enough to tip the balance.

- The Obscene Bird of Night by José Donoso was recommended by David Auerbach as relevant to my disgust project.

- The Anthologist by Nicholson Baker was on my list due to Rebecca's strong recommendation over at Of Books and Bikes; the combination of meditations on poetry and meta writing-about-writing is intriguing.

- A Pale View of Hills by Kazuo Ishiguro, in an extremely appealing new edition I haven't seen before. This and Nocturnes are the only Ishiguro I haven't read: his first and most recent.

- The Feast of the Goat by Mario Vargas Llosa comes highly recommended by Richard (maybe I should say recomendado con insistencia par Richard, as the post is Spanish-only), and I very much enjoyed the only other Vargas Llosa I've read.

- The Talented Mr. Ripley by Patricia Highsmith, with which I'm already halfway done and which has broken me out of the reading slump in which I spent most of September. Good old Highsmith: why haven't I read more of her?