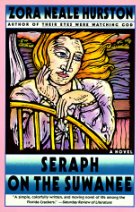

A former professor of mine once said, while discussing DH Lawrence's Lady Chatterley's Lover, that it's a book about female pleasure and female identity but not necessarily about female independence. The same can be said about Zora Neale Hurston's compelling but in many ways frustrating 1948 novel Seraph on the Suwanee. The character arc of the protagonist, poor white "Cracker" Arvay Henson, is in some ways an ultra-traditional one: she must learn to be the best wife possible to her husband, Jim Meserve. Nor is there anything progressive in the Meserve definition of a "good wife": early in the novel, Jim lays out for Arvay his vision of matrimony and gender relations:

Women folks don't have no mind to make up nohow. They wasn't made for that. Lady folks were just made to laugh and act loving and kind and have a good man do for them all he's able, and have him as many boy-children as he figgers he'd like to have, and make him so happy that he's willing to work and fetch in every dad-blamed thing that his wife thinks she would like to have. That's what women are made for.

Jim is not a caricature of Southern male arrogance. He's a sympathetic character; possibly the most sympathetic in the novel. He genuinely loves Arvay and he's an extremely hard worker, doing his utmost to live up to his own image of husband as reliable provider. What's more, he's up front about the contract he wants Arvay to enter into, although her initial reaction is "this deal is too good to be true," she eventually agrees. The rest of the book deals with Arvay's (very) slow realization that it's harder than she expected to live up to the terms Jim laid out, and with her even slower metamorphosis into a person able to hold up her end of the arrangement.

As a modern-day feminist fresh off of Hurston's Their Eyes Were Watching God, the most difficult thing to wrap my mind around here is the question of whether or not Hurston is critiquing Jim's worldview. It would be easy to jump to her notoriously controversial biography and her other books to feed conjecture on this issue, but sticking to the text of Seraph on the Suwanee: what is being presented here? Is Arvay to be taken as an unfettered agent, who enters freely into a legal and emotional contract with Jim Meserve and is therefore bound by love and honor to conform as best she can to his proposed marriage model? This is certainly the reading that suggests itself initially, complete with a happy ending for the couple when Arvay finally finds the courage, assertiveness and commitment within herself to be the wife Jim wants. On a subtler level, though, does the very length and difficulty of Arvay's journey imply a critique of Jim's expectations? Or of the social context in which the couple lives? It's a question on which I'm still vacillating.

A few examples of the trouble between Jim and Arvay. While Jim's initial portrait of married life seems to remove most agency from the wife (her decisions don't matter because she doesn't have a mind to make up; she need only laugh, act loving, have babies and get waited on—oh, and "make [her husband] happy"), Arvay soon finds that her own passive yet insecure personality is a surprisingly bad match for these expectations. It's not so easy, after all, to act loving, kind and carefree when her husband decides to delay a move she's desperate to make; or when he takes her religion in vain; or when she finds he's been running an illegal liquor still on their property for fifteen years and never mentioned it. It's not so easy to be the person who is supposed to like all the decisions, but gets to make none of them.

Like Lawrence's Lady Chatterley, therefore, Arvay is constantly holding back a part of herself, hoarding her own wilfulness against her partner and refusing to submit herself to his will. And because she's devoting so much time to resentment and doubt, she doesn't see all the things he's constantly doing to support her and even, one could argue, submit himself to her in turn. He moves to a new place because she wants to, and scrambles hard to establish himself there (she doesn't realize how hard he's working or how broke they are, because he never mentions it and does his best to hide it from her). She talks frequently about how scared it makes her to live next to a swamp, so he plots and plans a way to clear it (at which point she is confused about why he went to so much trouble). He doesn't insist on institutionalizing their violent son, because he sees how much it means to her (but she resents him for even suggesting her son could act violently). And so on. It's only after she lets go of her insecurities and directs her self-will toward supporting, rather than resenting, her husband that she is able to look outside herself and notice the ways in which Jim has been loving her with his actions all along.

But those actions, those unexplained and hidden actions. They're a source of the real frustration in the novel, and the possible source of any critique Hurston may have for Jim Meserve's marriage model. Because, seriously: this is a couple the majority of whose problems could be completely resolved with a few heart-to-heart conversations. If Jim were able to say, "I cleared the swamp because I knew it scared you and I didn't want you to be scared," or if Arvay could put aside her passive-agressive anger and really speak to Jim about her pain over his indifference toward their disabled son, and if the other person could just listen: ninety percent of problems SOLVED. Instead, sitcom-like, they indulge in three decades of unnecessary misunderstanding.

Jim dropped down and began to unlace his shoes. He got more quiet and took a long time before he looked up at Arvay again.

"So you really ain't got no notion why I wanted that swamp cleaned off, have you, honey?"

"Naw I told you. Not at all."

Jim jerked off first one heavy shoe and then the other.

"Well, maybe it'll come to you some day."

They didn't talk about it anymore and went on to bed.

Yes, heaven forbid they should talk about it. In Jim's mind, if Arvay doesn't see his motivation on her own, she won't truly believe or appreciate it if he tells her. On the other hand, his own glorification of female mindlessness and passivity makes a bad training for the kind of active, intuitive reading he's looking for here. What's more, Jim's gender formulations are those of the culture at large: this is a group of people who use the word "rape" for consensual, passionate adult sex—presumably an extension of the assumption that women need their decisions made for them. From my perspective, then, the tension in the relationship is largely due to Jim's insistence on an "actions speak louder than words" ethos, even in the face of Arvay's demonstrated inability to read actions. Neither partner is willing to train the other, and they have the bad luck to have ended up with communication styles that are actively opposed.

In the end, Hurston grants Arvay agency up to at least this point: while Jim says that women have no minds to make up, and that all that will be required of a wife of his is to laughingly receive bounty, he is actually looking for a much subtler understanding of how to read and perform acts of love and consideration, and perform them bravely and well. When Arvay finally breaks through her cloud of self-centered vagueness and commits to her husband, she likens her situation to a battle, if only a battle to stand by her man whatever he may do.

Nothing ahead of her but war, and she was ready and eager for it to start. She sat down again on the coil of rope and pleasured herself with the night. She sat and fed her senses with the light, the movement of the sea and the march of the stars across the sky. This was all hers until death if only she had the courage and the strength to hold it, and that she meant to do.

Hurston is one of those writers, like Willa Cather, whose work sits uneasily at the border of feminism—and nothing of hers I've read is AS uneasy at that border as Seraph on the Suwanee. As a person who believes submission and domination relationship models are inherently flawed, this is a challenging novel for me—not because I'm incapable of reading books that diverge from my personal ideology, but because I spent this reading unsure to what degree my concerns were or were not the concerns of this book. By focusing on the power dynamics of gender, am I a good reader or a bad one for Seraph on the Suwanee? I'm still not sure. But as usual, Hurston provides ample food for thought.

How interesting. My parents belonged to a generation, probably the last of a long line, who never talked at all. I once said to my mother, 'you've never actually asked dad for anything more than to pass you the salt, have you?' She agreed, but she didn't much like the question. That was the way things were - yup, completely incomprehensible, it seemed. And then when I'd had a child, and my husband and I were both very busy with our jobs, it was amazing to note how poorly we communicated, and yet we were big, big talkers. Marriage really can shut you up - for better or worse.

I'm wondering (and speculating, given I haven't read the book) how much it matters, exactly what the 'rules' are that husbands and wives lay down for each other. The marriage contract always turns out to include a lot of hidden clauses, that are no less important for being unspoken. My experience of marriage is one of eventually learning to call out those hidden clauses and to find out just how important or realistic they are. But I admit it took me years to realise this and to find a way to deal with it. I wonder whether we notice what those clauses are when we have a historical gap to bridge, because they seem more obvious, and often more unacceptable (and in this book, spelled out!). And yet I do think that marriage will keep on posing demands from husband to wife, from wife to husband, and couples will keep failing to negotiate them sensibly, rationally and lucidly. But I say all this and could be completely wide of the mark, never having read the novel. And many apologies if this is so!

I have to admit I've never read Zora Neale Hurston. I'd like to.

Litlove, you put your finger on much of what I struggled with throughout this read. These two sentences in particular:

The marriage contract always turns out to include a lot of hidden clauses, that are no less important for being unspoken. [...] And yet I do think that marriage will keep on posing demands from husband to wife, from wife to husband, and couples will keep failing to negotiate them sensibly, rationally and lucidly.

So true! If a partnership/marriage stops posing demands between the partners, it's a good sign that it's over. And I kept interrogating myself about the extent to which I believe it DOES matter what those specific clauses are, as long as both parties agree to them (or not). I certainly knew throughout the novel that this was not a contract I personally would ever enter into. But how relevant is that to what Hurston is trying to say? It was very difficult to get outside my own assumptions, which jarred against those of the book in a way both frustrating and fascinating.

There was also a lot going on in the novel that opposed actions to words, which added another level of complexity - how to parse Jim's insistence that women have no minds, when in practice he is deferring to Arvay much of the time? It brought up questions about hidden clauses UNDER the hidden clauses: is the rule that the husband is the decision-maker, or is the rule that both people agree to PRETEND the husband is the decision-maker when in fact they're collaborating? What bothered me about Jim and Arvay was that their rules seemed to disallow negotiation on Arvay's part - but maybe that was just a verbal rule, and actions speak louder than words.

What bothered me about Jim and Arvay was that their rules seemed to disallow negotiation on Arvay's part - but maybe that was just a verbal rule, and actions speak louder than words.

I haven't read this either, but I really like the idea that the actions of the story build the crucial clue as to the interpretation of the words of the text.

(Incidentally, my CAPTCHA for this comment is "powerful aingiu"; a phrase which, though not exactly words, seems somehow appropriate to the book in question.)

This sounds like it's both fascinating and frustrating. It's kind of fun to try to parse the gender dynamics of a novel, but Hurston does not make it easy in this case! I admire your determination to look just at what the text is telling you; it sounds very tempting to think about Hurston's biography and to go find what other readers and critics have made of it.

Hurston definitely does not make it easy—especially for someone of my particular outlook. I think someone who went into the novel accepting the proposition that the husband should be the dominant partner in a marriage, would have less of a struggle with it. I think I would have made the assumption that Hurston was all in favor of that outlook had I not read Their Eyes Were Watching God, which I suppose is the unwritten source of influence in this entry despite my attempt to stick to the text of Seraph!

I had similar problems with this novel in a seminar class in grad school where I thought some mistakenly took the ending as an assertion of feminine choice/power. I disagreed but was not as bothered by that aspect as much as this contractual view of partnerships. Soulless and very sad to me. I appreciate the way she developed the story but was too wary of that content to ever allow myself to relax into the read.

Oh wow, I certainly disagree with that reading of the ending, as well. More like a final acceptance of her subservient position (which does, of course, take a certain kind of strength). I'm not sure I totally agree about the soullessness of the relationship-as-contract...Hurston did at least portray it as a living contract, I suppose. But the evidence of the assumption of female brainlessness made me sad, and the vicious cycle of women becoming infantilized because everyone treated them like children.

Like Litlove, I haven't read the book, but I agree with her that the hidden compacts of marriage are something that are negotiated, often silently, between spouses over the long haul. I'm not sure that one ever really knows what goes on inside another's marriage which is what makes reading books about a marriage so intriguing. It is that distance -- whether generational or not -- that gives us insight into what boundaries and constraints we can accept. Although my generation is much different in its expectations of marriage, children, careers, choices than my parents I often wonder how much different it really is to learn to live with another as a unit. The goals may be different but I'm not sure that difficulties in compromising are any less.

With regard to the difficulty you write about in trying to make sense of the text and author's intent: I'm glad that you wrote about this. I too often times have this struggle with some works. It's like a puzzle to me, taunting me to work out a solution that may not exist. There are some works that I feel I just need a fixed mark so that I can find my way through the text. It is exactly that kind of work that I find challenging and that I like to read because it makes me think and to work for the reward, even if it is something much different than an author might have originally conceived. The text should be it's own reward, but sometimes I find more in the challenge to work out that understanding.

Thank you for such a thought-provoking commentary on this book.

It is exactly that kind of work that I find challenging and that I like to read because it makes me think and to work for the reward, even if it is something much different than an author might have originally conceived.

Yes, I agree. And I also find that in these slippery cases it's particularly useful to read in the context of a conversation, so I'm able to bounce ideas off other people and get a bit of help "positioning" my own response. So, thanks for your insightful comment!

Yours and Litlove's points about the compromise inherent in any long-term relationship are something that were very much in my mind throughout this read. Hurston was obviously invested here in portraying a marriage "warts and all," and any such partnership will involve words and actions that the partners wouldn't like to see quoted back to them or preserved forever in print. And as you say, the process of accommodation when learning to combine one's life with that of another person is largely the same regardless of the goals. I certainly did find, though, a hard line beyond which I personally couldn't compromise, which is the ideal of equality and mutual intellectual respect.

I found this one so challenging too, but ultimately in a good way! The gender politics were fascinating, and like Litlove I assumed their inability to communicate was a sign of the times. I remember doing a post about it, because a couple of the sex scenes in particular disturbed me.

I remember your post on this, Eva! I had just bought the book at the time so I definitely recalled your points about the use of the word "rape"—which I also found troubling.

I assumed their inability to communicate was a sign of the times

A sign of the times yes, but in Their Eyes Were Watching God we see that different groups of people living in the same place and time period were able to craft much different relationship dynamics. And also, in that book, there's a clear critique of a domineering, husband-centric marriage that uses the woman as a show piece and ends up stifling her. That's what was especially challenging for me to wrap my mind around with Seraph: Jim speaks as if he would be a copy of Joe Starks. But he's really not, which is a big part of the "actions speak louder than words" thread running through the novel.

I'm not sure I'll ever read this book, but I sure enjoyed you trying to puzzle out what we are supposed to make of it. It would be so easy to completely dismiss it as anti-feminist, but clearly there is more going on than that. What, exactly, that might be is part of the fun of reading, yes?

Haha, glad you enjoyed the post, Stefanie. Yes, the fun and the difficulty is definitely in figuring out what more might be going on—or even, what different. There were times during the reading when I was unconvinced that feminism or a lack thereof were even relevant, somehow.

Given the uncertainty of Hurston's message here, Emily, I'm curious as to whether it would have changed your opinion of the book had it been written by a man instead of a woman. Any thoughts on that? P.S. I have Their Eyes Were Watching God in my TBR, but I'm not entirely sure I didn't already read at least part of it years and years ago for a class. If I did, I must have been cramming rather than reading for pleasure. Rather embarrassing, I know...

The $64000 question, isn't it. As much as I tried to stay away from inter-book comparisons in this post, I think that, man OR woman, if it weren't for Their Eyes Were Watching God I would probably not have given Seraph nearly as much latitude with its politics. If it had been by a man who had also written Their Eyes...I don't know. I can't pretend it wouldn't have added another layer of resistance in my mind. Although actually, I almost think I would have been more impressed by it were it by a male author, just because of the level of introspection and attention Hurston gives to Arvay's emotional journey.

If it were by a man who HADN'T written Their Eyes I probably never would have picked it up.

So there you have it: my gender biases laid bare. :-P

I think I'm interested in this because I love Their Eyes.....but it sounds like a frustrating read. I'm curious though to see the dynamics your talking about.