I was feeling a bit under the weather after a long weekend of festivities relating to my cousin's wedding, so figured it would be an ideal time to peruse some of the lovely art books I picked up in France. These two titles, François Morellet: L'esprit de l'escalier and Cy Tombly: The Ceiling, are matching Louvre-produced editions that focus on installation pieces commissioned by the Louvre from contemporary artists, and incorporated into the architecture of the museum. (I wrote about seeing both these pieces back in May.) Both books are slim, handsome little hardcovers, appealingly produced, with fold-out pages depicting the featured pieces and a nice selection of supplementary text and images, including brief historical essays about the history of the spaces in which the pieces are installed. Both editions are edited by, and feature interviews with, the Louvre's Curator and Special Advisor on Contemporary Art, Marie-Laure Bernadac. I'll be posting on the first of these today, and the second tomorrow or the next day.

François Morellet: L'esprit de l'escalier

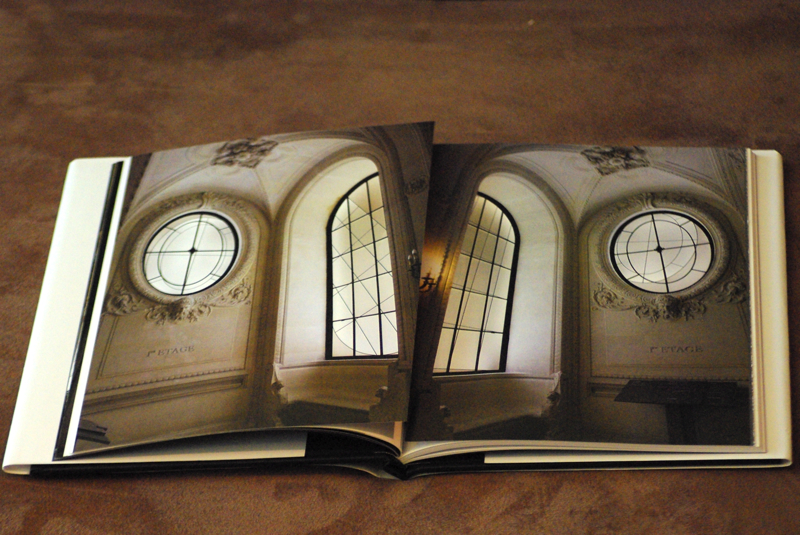

I suspected as soon as I saw the playfully modern leaded-glass windows in the bays of the Lefuel staircase, that I would appreciate the sense of humor of their creator, and this volume only confirmed that suspicion. Morellet comes off in his interview, and in the other works of his I've seen, as a witty, unorthodox person, the first to poke fun at himself along with the institutions and assumptions of the art world. When Bernadac asks him whether he, a self-professed auto-didact, frequented the Louvre as a young man, he exclaims "Voilà la question que je redoutais!" ("The question I was dreading!"), and goes on to explain that, in his youthful rebellion, the Louvre seemed to him a bastion of stuffy authority, a place teachers told him to go rather than one he chose to frequent. It was only later that he discovered inspirational geometry and repetition in the museum's collection of Pacific Islander Art. (He finds the same qualities inspiring in the Islamic and Moorish art of the Alhambra and the Middle East).

Morellet's interest in geometry and repetition leads to an interesting exchange about the (in many ways arbitrary) division between "fine arts" and "decorative arts," which as a textile artist is always an interesting conversation to me. Morellet says that

[U]ne oeuvre qui est considérée par le spectateur comme vide de tout message, qu'il soit clair, occulte ou inconscient et qui d'autre part, circonstance aggravante, ne porte aucun trace des précieuses imperfections de la réalisation manuelle n'aura pas le droit d'entrer dans le monde des "beaux arts." Elle sera reléguée dans la section "art décoratif," qui a ses propes écoles et ses propres musées. [...] D'ailleurs, apparaît une autre raison de ne pas admettre ces oeuvres dans la catégorie "beaux-arts," c'est-à-dire la grande place laissée à la géométrie, à la logique, aux systèmes..., c'est-à-dire à ce qui s'approcherait un peu de ce que l'on nomme bêtement l'intelligence.

[A] work that the viewer perceives to be empty of any message, be it obvious, concealed, or unconscious, and in addition—aggravating circumstance—does not bear any trace of the precious imperfections of hand-production, will not be accorded the right of entry into the world of "fine arts." It will be relegated to the "decorative arts" section, which has its own schools and its own museums. [...] For that matter, there is another reason not to admit these works into the "fine arts" category, which is the importance accorded in them to geometry, to logic, to systems..., that is to say, to areas approaching that which we stupidly call intelligence.

This aversion to thinking of the fine arts (visual arts, at least) as averse to "intelligence" is an interesting point, and probably connected with the widespread desire to see "art" as the product of some kind of miraculous god-given inspiration or instinct, rather than as a craftsmanly process requiring thought and practice as well as intuition. Fabric-printing and book-binding, though—people are fine with the idea of those as originating in the human realm. Morellet blurs these lines, being considered a fine artist but working primarily in the realms of logic, geometry, and humor, rather than in any kind of confessional style.

So too, Morellet has interesting things to say about permanence and deliberate anachronism. The "L'esprit de l'escalier" windows are executed with a leaded-glass technique that originated in the middle ages; this medieval technique is used to superimpose a skewed version of the 19th-century grillwork that already existed in the windows. Adding another temporal layer to the mix, the entire piece was planned in 2008 and executed in 2009. Morellet says that this mélange of eras "pleases him greatly," and I can only agree—the windows become a palimpsest of different artistic traditions, which is very fitting considering their placement in the world's foremost bastion of Western art. He goes on to say that many of his installation pieces have been time-limited, which contrasts with the permanent quality of "L'esprit de l'escalier." He makes the point, though, that so-called permanence is often anything but: of the hundred or so "permanent" installations he's done, the majority have already been swept out of existence. Not that this is a new observation ("My name is Ozymandius, King of Kings," etc.), but it is a striking figure: over half the "permanent" works of a living artist no longer exist. It makes a person think a bit differently about artists whose work is explicitly ephemeral; perhaps they're simply more realistic about the final fate of all works of art.

Lastly, I was ticked by Morellet's thoughts on creating for a select audience rather than le "grand public." He says that he likes his installation pieces to be discreet, almost secret, only perceptible to the small number of people who are attuned to his work.

De toute façon j'essaye pour ces intégrations, surtout si elles se trouvent dans des lieux très tréquentés par un public non spécialisé, de rester discret et idéalement de n'être visible que pour mon cher public un peu spécialisé.

Anyway, I try with these integrations, especially if they're located in places frequented by a non-specialized public, to keep them discreet and ideally invisible to everyone except my dear, particular public.

My translation isn't great—there's no sense that Morellet's ideal audience is a group of specialists in the professional sense, just that he wants to make art that is a bit low-profile, so that only people prone to delighting in details and appreciating his sense of humor will notice them, and everyone else can go about their business unmolested. This is an idea I love—that of a piece of art hidden in plain view, appreciated by those who take the time to notice it. A "specialized" audience need not be an elite one—indeed, Morellet himself is self-educated, and there is nothing about "L'esprit de l'escalier" that privileges classical education. Rather, it selects for a group of people who may be disparate in other ways, but who appreciate a subtle, humorous skewing of the expected norms. Morellet is an artist for whose work I will continue to look out.

Fascinating information about the windows and the artist! I like the idea of discreet art, hiding in plain view, waiting to be noticed and the elements of surprise and delight that this plays on. I also like the idea of art crossing boundaries.

I like the idea of discreet art, hiding in plain view, waiting to be noticed and the elements of surprise and delight that this plays on.

Yes! Me too. It's the opposite of the stereotype about modern & contemporary visual art being confrontational & "in your face." Which can also have its place, but Morellet's approach resonates with me.

Does the book talk about its title? Only I know the phrase 'l'esprit de l'escalier' as meaning the things you think of and wish you'd said as you are walking away from a confrontation. It's SUCH a useful phrase and one for which there is no obvious English translation. I just wondered how he was using it in relation to his art. I, too, love the idea of art biding its time quietly, waiting to be seen. Is that what the title refers to, when people walk away and then think, hang on a minute, what did I see there that was so lovely? I don't know, just having fun speculating!

Litlove, the book does address the title but maybe not exactly in the way you're looking for. Bernadac asks Morellet about his love of word play and puns, and how he often incorporates them into his titles (this piece, for example, is called "Geometree"). He has a funny line about how his obsession with wordplay has taken over his life and has at times been "very hard on his friends and family." Apparently the wordplay has invaded his titles gradually, partially as an attempt to signal that he didn't take himself overly seriously. But he doesn't exactly explain the connection between "l'esprit de l'escalier" and the piece itself—I think your guess about turning back for another look at the half-glimpsed windows is a good one. And in a more literal way, I suppose that putting this piece of art in the staircase is providing more of a spirit for it, making it wittier.

What does L'esprit de l'escalier roughly translate to? Litlove's comment has me intrigued.

It literally means "spirit of the staircase" or "wit of the staircase," and it's an idiom for just what Litlove describes: when you think of the perfect comeback or bon mot after you've already left the party/encounter/etc. I hate that! :-P

"This is an idea I love—that of a piece of art hidden in plain view, appreciated by those who take the time to notice it." Quietly beautiful. An idea I also love. Think that we have had this conversation before but my grandfather was a master craftsman, and he built the most thoughtful, elegant and well-constructed things imaginable. Growing up with him left me not only equipped with practical skills often missing in today's society but also always on the lookout for the smallest details - is that door pieced or from a whole piece of wood, how is that drawer constructed, etc. This book appeals to me.

Are these the same grandparents who bequeathed you the annotated edition of Montaigne? They sound like amazing people. I'm more attuned to the details of garment construction than those involved in other crafts, but I'm gradually building my knowledge base. Hopeful that I can come to appreciate more & more of the artful details hiding in plain sight.