Those of you who read my comments on the first few chapters of Carola Hicks's awkwardly-titled The Bayeux Tapestry: The Life Story of a Masterpiece, are probably wondering whether I was ever able to get over my yearning for a close reading of the Tapestry, and enjoy this book for what it is: a "biographical" account following the artifact through the thousand years since its composition, and all of the social and ideological battles that have been fought over and around it during that time. And the answer would be, more or less, yes. I'm still interested in reading something geared more toward artistic analysis of the Tapestry—something that "fondles its details," as Nabokov might say—but Hicks's approach proved quite juicy as well, and brought up some interesting points of consideration.

She has plenty of material to work with. The Bayeux Tapestry has simply been around longer than most non-classical works of art in the Western canon, and when you combine that with the fact that by its very nature it exists on the boundary between two nations—depicting as it does the invasion of England by the Normans, a people from what is now the northwest corner of France—it's not surprising that the work has become the site of a number of nationalistic and ideological struggles throughout the years. As "antiquarianism" (the 17th and 18th-century precursor to anthropology) gained ground, for example, the Tapestry was the subject of a hilarious series of sniping pamphlets between Frenchmen and Englishmen, who argued bitterly about whether the thing was a "French" or an "English" artifact. The fact that the modern "English" have long incorporated Norman heritage into their identities; that "Normans" were not exactly French to begin with; and that the Tapestry's own narrative is remarkably sympathetic to those on both sides of the Conquest; did not stop pamphleteering gentlemen of leisure from interpreting the embroidery in the most jingoistic terms, such as in this nuanced reading from 1742:

We see the faithless, inconstant and perfidious disposition of the French and their behavior towards us. We see, then as now, the genius of the English, brave, generous, honest and true. We may learn hence never to trust the bonne foy of that nation, but expect they will still be the same, as from the beginning.

The question addressed in my previous posts, about who did the actual embroidering on the Tapestry, was actually a topic of hot debate during this time. The French contingent attempted to emphasize the work's Frenchness by claiming that it was embroidered by the French queen Mathilde (wife of William the Conqueror), whereas the English contingent tried to emphasize the opposite by claiming that it was embroidered by English monks or nuns, on English soil. As far as I can tell, this debate is still very much alive, with no one definitive interpretation emerging—although the theory that it was commissioned by Odo, designed by a monk and executed in England seems to be the most popular.

For their side, the French used the Tapestry when convenient to serve as a model for current events. Napoleon, for example, had his arts-and-culture man Denon arrange an exhibition of the Tapestry in the newly-converted Louvre, in order to drum up popular support for the idea of a Napoleon-led invasion of England. He even went so far as to plant pieces of information in the press (which he controlled) to the effect that a comet had recently been seen in the skies—just like the one in the Tapestry that heralds the downfall of Harold and the arrival of William the Conqueror. Clearly, whatever Napoleon wanted to do must be sanctioned by divine right.

In a similar but slightly stranger vein, Heinrich Himmler and the Nazi party were extremely interested in the Tapestry during the Second World War. As far as the Nazis were concerned, the Anglo-Saxon heritage of the pre-Conquest English made them more or less Vikings, which meant that they were more or less German. (I'm betting they did not ask a Norwegian's opinion on this.) Which, in turn, meant that the Bayeux Tapestry could be "reclaimed" as an example of "pure Aryan" art, and removed back to Germany to serve the cause of Nazi propaganda. It was only through the resistance of a few individuals (both German and French), and a series of lucky breaks, that the artwork survived the War and remained in France. This Nazi angle is one of the stories that Hicks is very interested in telling: she opens the book with an anecdote about Himmler ordering the Tapestry removed to Berlin in the last days of the War, and her chapters on WWII are longer and more detailed than most others. Personally, I found that they dragged a bit, but I must admit to being a little "Nazi-ed out" in my reading, so others may feel differently. Not, of course, that Nazis and the Holocaust should not be written and talked about, but I've read a LOT about them and at this point am more interested in other historical periods.

One of the aspects of the book I did find reliably fascinating was Hicks's examination of the social debates taking place around the tapestry: in particular, its relationship to feminism and art theory. In the early Victorian era, when the first rumblings of an organized feminism were afoot, attitudes to embroidery within that nascent movement were very conflicted. For some early feminists, like Mary Wollstonecraft and Mary Lamb, embroidery was pointless, infantilizing busy-work, taught to upper- and middle-class women in order to signify that they had nothing important to do and so could afford to waste their time on trifles. These women agitated for a female education closer to that received by boys, emphasizing physical and mental activity over sedentary domestic arts. A different contingent of early feminists, however, looked to the Bayeux Tapestry and other works of needle art as a uniquely female sphere of artistic endeavor—one often unfairly dismissed, yet in truth equal to the male-dominated mediums of painting and sculpture, and in need of rehabilitation in the public eye. Both of these arguments are fascinating, and remarkably similar to debates still raging among feminists in the fiber arts world today. Neither side presents a case I can wholeheartedly agree with, but both provide food for thought, particularly as they intersect with issues of class. (And just to add spice to the mix, still other Victorian critics claimed that the naked figures in the margins of the Tapestry proved it COULDN'T have been embroidered by women, as their native delicacy would never have permitted such lewd subject matter.)

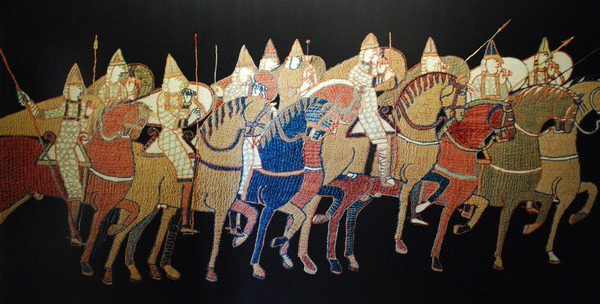

The other unexpectedly thought-provoking thread in Hicks's book was her tracing of aesthetic reactions to the Tapestry through time. In the 18th and 19th centuries, for example, most people were extremely put off by details that I would not even think to criticize: for example, that the colors in the Tapestry are not "true to life," or that a single horse is often portrayed using different colors. See below, for example; the inner side of a horse's back leg is often embroidered in a different color, giving a sense of depth without Renaissance-style perspective.

Similarly, 18th and 19th-century viewers were alienated by the lack of classicism in the style of the Tapestry. They equated "good art" with the ideals of Greek and Roman statuary and the painting that imitated it—illusionistic perspective, clothes that drape "realistically" over a muscled body, and so on—and in many peoples' minds there simply was no other yardstick by which to measure a piece of art. Accordingly, when people started attempting to revive the reputation of the Bayeux Tapestry, they made obsessive parallels to classical art; the only way they could think to elevate public opinion of the Tapestry was to uncover previously-unnoticed similarities to the Greek and Roman style. Only the most sensitive art critics of these times, among them John Ruskin, were able to evaluate the Tapestry on its own merits rather than attempting to imagine it into being as the Roman frieze it so plainly is not. It's fascinating to think that modern viewers, long accustomed to the playful abandonment of perspective pioneered by Van Gogh and others, and the anti-realistic use of color in everything from Picasso paintings to TV commercials, can more easily appreciate the artwork of the Tapestry than people for several centuries before us.

So, despite the occasional slow section, Hicks's Bayeux Tapestry was more than worth my time. I have another, lavishly illustrated book of academic papers on the Tapestry, so hopefully I'll get my fill of both its biographical and textual details.

The Bayeux Tapestry is damn cool. I am in two minds about this book though -- on one hand, I love reading about how people viewed various people and things and events at different times in history. But on the other hand, I know zero things about tapestry. Would that impede my enjoyment?

I wouldn't think a lack of technical knowledge would impede your enjoyment at all, Jenny. In fact, this book seems like a good choice given that it's really more about the Tapestry's role in history over the last 1000 years, how people viewed it and tried to use it to further their own ends. There's almost nothing technical in it, although Hicks does describe how the embroidery was most likely done and the general artistic style. But I don't really know anything about embroidery or tapestry and I had no trouble following! :-)

Very interested to read this. Carola Hicks had a book out recently about the stained glass windows in King's College and I was quite tempted to read it. Given how much you enjoyed this book, I will definitely try to get hold of a copy now. I love reading you on tapestry, but I don't think I'd get through a whole book on it - still, thanks to your informative post, I don't have to. :)

I liked Hicks's style enough that I would definitely read another book of hers if the subject appealed, and stained glass sounds like a good candidate! I sympathize with feeling interested enough in a subject to read a blog post but not a whole book—our reading time is so limited, after all.

Great review! This sounds like a very interesting book.

Thanks! It was pretty fascinating.

This sounds like a book I would enjoy reading - I'm fascinated by how various historical eras reinterpret and co-opt the past. It's true, as you say, that debates about "women's work" / fiber art, etc. are still going on. That's almost embarrassing!

Haha, I know, it is a little embarrassing. Although, being very familiar with these debates as something characteristic of modern feminism, I was kind of impressed to see them cropping up so early (late 1700s). And if you're interested in the versioning or different perspectives on a single work of art over the course of years, I'd definitely recommend this book. It's kind of amazing the number of different ideological roles a single piece of linen has played!

So interesting hearing about all you've learned in regards to the tapestry! I found your final comment on how modern viewers can more easily appreciate the tapestry because of Van Gogh, Picasso, etc., fascinating. I never would have considered that. I realized that when I first looked at the horse image I didn't see anything unusual about them and when you pointed out that single horses were done in more than one color I looked again, and so they are. So I think your observation spot on.

I'm glad you found that part interesting, Stefanie, because it was an idea that had never occurred to me before reading this book. But seriously, commentator after commentator kept putting down the tapestry because (e.g.) "there are blue horses!" or "the horses are more than one color!" and it really made me think about how we're conditioned to see & process art. I actually think medieval and modernist art are surprisingly similar in a lot of ways—the ubiquitousness of asymmetry, for example.

This sounds fascinating! Despite the fact that I'm perpetually Nazi'ed out. ;) I was disappointed with a historical fiction book I read centered about the tapestry (Needle in the Blood), so I think a big nonfiction book about it instead is just what I want!

Haha, glad to know I'm not the only one Nazi'd out, Eva. And yeah, Hicks devotes a chapter to the various historical fiction, theater etc. that's been devoted to the Tapestry...I must say it didn't inspire me to go out and buy any of the books mentioned. Nonficiton was rewarding, though!

I have what may be a related work, 1066: The Hidden History in the Bayeux Tapestry by Andrew Bridgeford, but of course I haven't gotten around to reading much of it after buying it a few years back. Will have to compare notes with your review's book if/when I ever get around to it. In the meantime, your report about earlier viewers feeling all tweaked about the lack of "realism" in the artwork sounds suspiciously like the amusing blogger complaints I occasionally run into about books that don't follow a carefully mapped-out 19th century psychological realist roadmap with a linear progression that's predictable well in advance. The horror! The horror!

I must admit that the comparison crossed my mind as well. In fact I originally ended with a whole other paragraph that basically took my sentence "modern viewers [...] can more easily appreciate the artwork of the Tapestry," and added a tabloid-style "OR CAN THEY?????" to the end of it. But then I felt it was perhaps off-topic. ;-)

It does bring up some interesting questions about one's priorities for art-consumption, doesn't it? What percentage of people are inspired by departures from the mainstream, and what percentage are threatened by them? And when does "the mainstream" become so antiquated that it's closer to modern experimentalism than anything?

This book sounds really interesting, even if it wasn't exactly what you were looking for. I love how much history it's possible to glean from the story of an object, especially a work of art. It's such a fascinating way to learn about many different aspects of history.

I really love object- and artifact-based history, too. Laurel Ulrich's The Age of Homespun is one of my favorite examples of that methodology—she takes pedestrian items like spinning wheels and painted chests, and uses them to tell fascinating snippets about early American life. I tend to find history especially interesting when it focuses on everyday people, rather than the famous movers & shakers.