I must admit that there's plenty of free internet here at the big splurge of our trip, the Grand Hotel Cabourg. So I have no excuse for skipping a day except the truth: that we were too busy relaxing to do anything as effort-intensive as blogging! Cabourg is the town, and the Grand Hotel the hotel, on which Proust modeled the town of Balbec and the hotel where Marcel stays with his grandmother and meets Albertine and Robert de Saint-Loup in A la recherche du temps perdu, and the level of old-school luxury here is everything I could have hoped for. They really do up the Proust connection, too: madeleines on the pillows and lime blossom tea in the drinks closet. (In another context I might feel like this was cheap pandering, but really I'm just pleased that enough people are still interested in Proust for him to be a tourist draw.) Listening to and gazing at the surf through the big French doors onto our balcony while stretched out on the crisp white linens is intensely relaxing. But I'm getting ahead of myself...

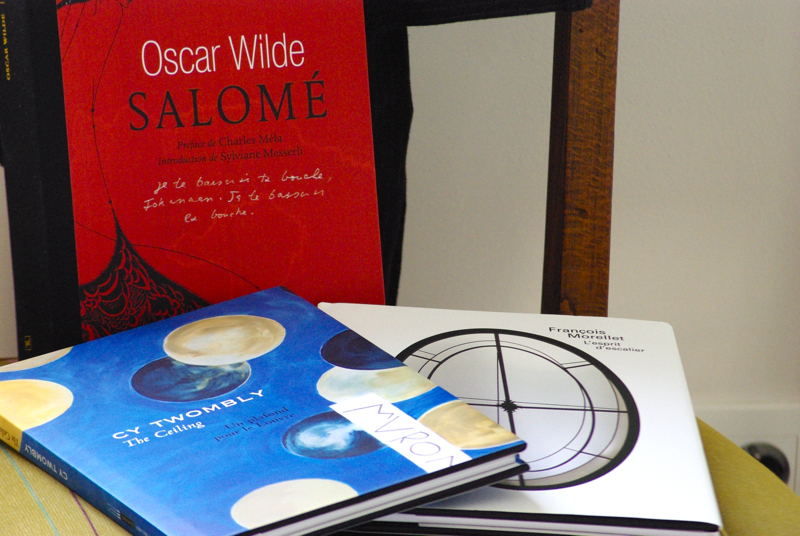

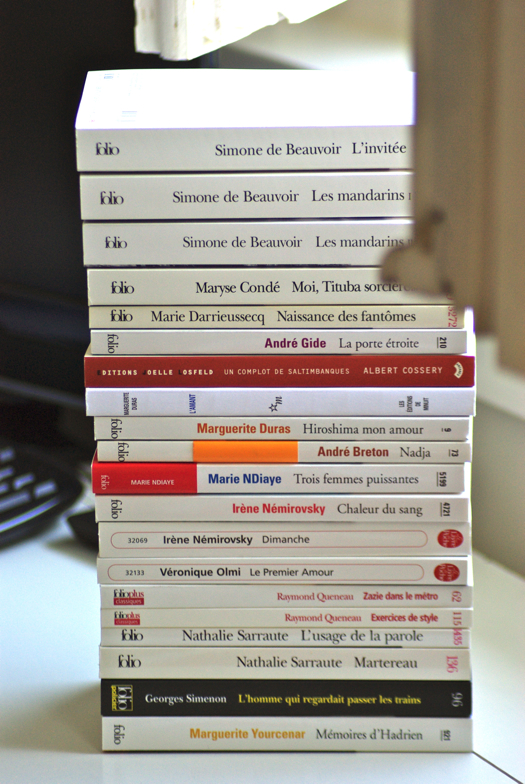

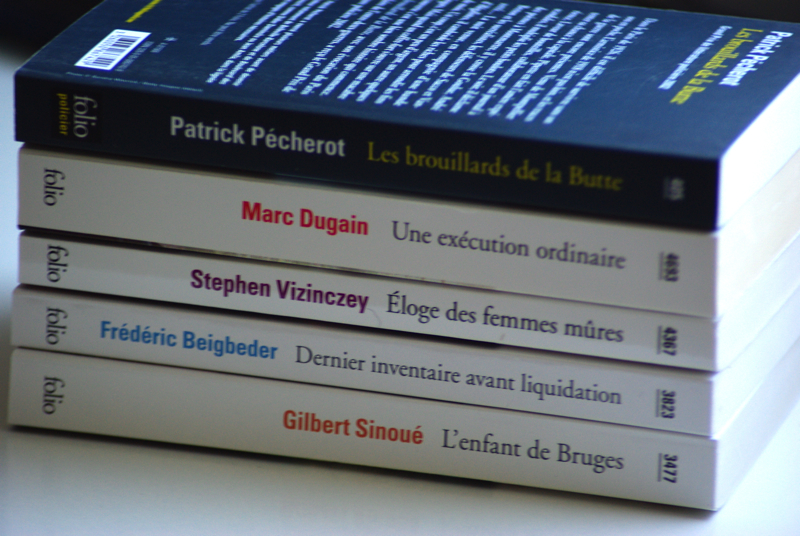

I am big enough to admit that my mom was right: I should have shipped some of those books home from Paris by post, instead of packing them all into my suitcase. Fitting them in wasn't a problem; the issue came when I tried to pick the thing up to carry it down the four flights of spiral stairs descending from our apartment. After that, we faced the dilemma of whether to taxi, métro, or walk to the Gare du Nord, where we were to pick up our rental car. As backward as it probably sounds we opted for walking—neither of us could envision heaving our bags over the narrow métro turnstiles, and it rubbed us the wrong way to spend the euros on a taxi. Trading off bags, we managed to get ourselves and our stuff back through the touristy sex-shop area on Boulevard de Clichy and down to the Europcar counter, where they entrusted us with the keys to a little silver Fiat. It was very exciting, Americans as we are, to launch out on the road trip portion of our trip—and, as much as I enjoyed Paris, to get out of the hustle and bustle of the city.

I was a bit nervous about driving in a foreign country, particularly the "getting out of Paris" part, but it wasn't bad at all. Of all the places I've driven or been in a car, I think Paris is scarier than Portland (where there are actually stand-offs of politeness between drivers who both want to cede the right-of-way to the other person), but not nearly as bad as Boston (where I feel like all the other drivers actively want to kill me) and nowhere CLOSE to Madrid (where the cars and motorbikes seem to operate according to a different set of physical laws than the ones I'm used to). We left around noon, which is a nice time of day traffic-wise, and were soon hurtling along surrounded by the rolling green hills of the Norman countryside at a startling-sounding 130 on the speedometer (actually only about 80 miles per hour). We headed to Rouen, about an hour northwest of Paris, where we stopped and had lunch at an outdoor cafe, and then wandered around the old center of the town that surrounds the cathedral.

Rouen on a Sunday, when most shops were closed and most people unhurried, was just the respite I needed from the tight-packed activity of Paris. We strolled along the medieval boulevards and around the cathedral itself—the very place where Flaubert's Emma Bovary attempts half-heartedly to ward off her would-be lover Léon before surrendering to him during their extended carriage ride. (This modern stained glass, added to the cathedral in the 1950s, struck me as a particularly appropriate illustration at this point.)

Rouen Cathedral was apparently damaged during the bombing of the Second World War, and is also in the midst of extensive restoration right now. Between those two factors, there is substantially more light inside it than in your average medieval cathedral. Many of the windows, which I assume were originally darkly colored stained glass, are now white glass, which means shafts of direct sunlight fall on the busts and columns of the cathedral. This unfiltered light lends the cathedral's interior a surprisingly sweet, down-to-earth quality that I really liked, regardless of whether the effect was in any way intentional.

We wandered into the cathedral by a side door, whose arched doorways featured carvings of all kinds of mythological and/or monstrous creatures: pig-headed women, bats playing stringed instruments, and all kinds of fascinating characters. This figure looks like the be-wimpled head of a woman with the body of a serpent-chicken? Some of them got fairly grotesque, and it was another reminder of the medieval love of, and belief in, the bizarre, which I was writing about a few days ago.

Yesterday could not have been more beautiful in this part of the world, and we strolled around enjoying the warm sunshine and the accordion music that drifted faintly down the narrow alleys from the main square. Eventually, we made our way back to our car and drove to the Grand Hotel Cabourg. As I said, this is the splurge of the trip, and it definitely measures up. A recently-refurbished yet still beautifully old-school seaside resort, it perches above the Atlantic and a wide pedestrian boulevard called the Promenade Marcel Proust, down which couples, dog-walkers, and parents with toddlers stroll in classic striped seaside gear.

Our balcony overlooks the promenade. Yesterday evening, and again this morning, we sat at our little table and people-watched while breathing the salty sea air. (We decided the smell is halfway between the Pacific of the American west coast and the Atlantic of the east.) This morning we donned the cushy terrycloth robes provided by the hotel, and lolled about on the balcony while dipping our madeleines into our lime blossom tea and generally being super-dorky yet very happy Proustian tourists. David kept making jokes about how he was afraid his long anticipation would mean he couldn't enjoy the experience, and I saw little Marcel in every kid on the esplanade.

We took things very easy today, having a much-needed long sleep this morning, then venturing out to explore the little seaside town and take a long walk on the beach. Because of my childlike tendency to run into the ocean when I find myself close to it, I didn't take my camera on our walk, but today the weather was overcast and we even got a light rain during the early afternoon, when David and I were closeted in a cozy pizza shop that made surprisingly excellent pizzas and galettes and played a funny mixture of 90s brit pop and American oldies. I had expected that the overcast weather would mean a familiar beach-going experience; after all, I love to go to the Oregon coast in the overcast and rain (which is most of the time), so I suited up in sweater and rain jacket as we were leaving on our walk. I was wrong, though; the skies here may look like the gray Oregon Coast skies, but the water is FAR warmer and there was almost no wind, which meant the entire experience was disconcertingly mild. I was soon carrying my sweater and rain jacket and walking around in my shirtsleeves.

I could easily envision the work of Proust's fictional painter Elstir as we walked along the beach under the overcast skies; the fishermen were out with their nets and their hip-waders, and dogs snuffled around the washed-up collections of shells and seaweed looking for something illicit to eat.

As we strolled along, we got to talking about the fact that six couples we know have had babies within the past year, and all six babies are boys. This undiluted crop of boys struck us as unlikely, and we debated a bit about exactly how unlikely it is that all six kids in a given group would end up male. As neither of us remember much from our statistics courses, we didn't get far until we stopped and actually worked out all the possible boy/girl combinations in the sand. David snapped a picture with his phone of our important work:

As far as we can tell, with six babies there are 64 (or, it seems, 26) different possible boy/girl combinations, and only one of those results in all boys (or all girls). So there's only a 1 in 64 or 1.5% chance of all boys, without even taking into account that slightly more girls are born than boys. We should have taken out a bet before all our friends had their sons! What makes all this especially funny is that one of the mothers in question is a statistician. No doubt she could have helped us out.

After that grueling math break, we returned back to the lap of luxury for an extremely fancy dinner in the restaurant of the Grand Hotel, during which I got crayfish ravioli, David got a sole that was de-boned for him at the table, and we shared a bottle of red from Chinon, over which we enjoyed an animated conversation about Virginia Woolf and the politics of the Harry Potter books. Good times!

Tomorrow we're off to see the Bayeux Tapestry and Mont St. Michel. Although I'm tempted to just stay on my balcony listening to the surf and drinking tea.