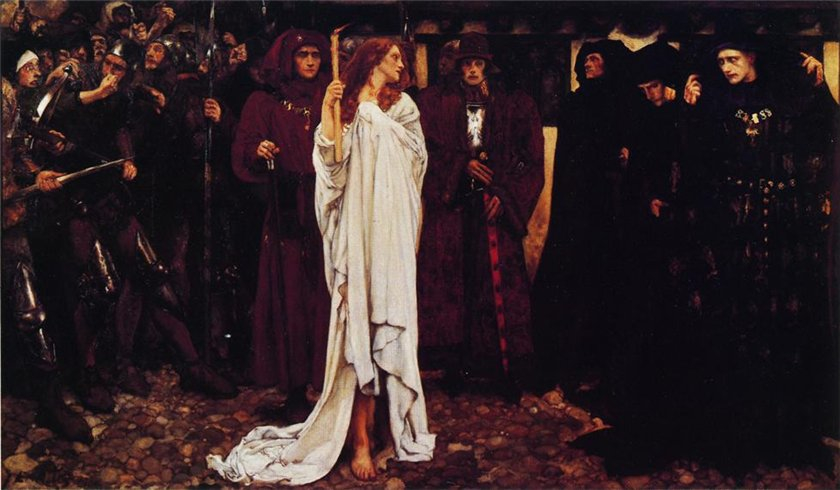

In a coinage which has achieved fame in the annals of internet film criticism, Onion AV columnist Nathan Rabin discussed "a character type I like to call The Manic Pixie Dream Girl": "that bubbly, shallow cinematic creature that exists solely in the fevered imaginations of sensitive writer-directors to teach broodingly soulful young men to embrace life and its infinite mysteries and adventures." Well, not solely in the minds of film writer-directors. We bookish folk must admit that Manic Pixie Dream Girls enjoy a parallel history in written fiction, from Leslie Burke in Katherine Paterson's Bridge to Terabithia to (it could be argued) Henry James's Daisy Miller. In both Paterson and James, as in MPDG films, the narrative focus is on the effects of these unorthodox, energetic girls on the male narrators, rather than on the inner lives of the girls themselves. In both cases, the girls cause the males to question their preconceived notions. And in both cases, of course, the girls must die, never to lose their effervescent, youthful energy; never to become mature women; never to threaten the fetishized memories kept inviolate by the men they leave behind.

Anna Gmeyner's 1938 novel Manja is a lesser-known example of the MPDG genre, and it really goes for broke. Rather than merely allowing its vibrant, imaginative young heroine to transform the emotional world of one mopey young man, it has her do it for four of them simultaneously: Karl, the son of Communist activists; Heini, child of educated leftists; Franz, son of a stupid, cruel thug who rises in the ranks of Nazi officialdom, and Harry, the half-Jewish child of a banker whose power is on the wane. The five children form the kind of predictably unpredictable band beloved of childhood fiction (the smart one! the cowardly one!), and yet I must say that Gmeyner pulls off their interactions with a certain amount of subtlety and interest. This interest dwells, not so much in the development of the individual characters, who are fairly transparent "types," but in their interactions and the ways in which the rise of Fascist power affects the group dynamic. In the interactions of Karl and Franz, for example, one can trace the similarities in the militarism of both boys' upbringing, despite their positions on different sides of the political spectrum. When the children play Indians, Harry is cast as the noble chieftan, husband of the princess, while Karl and Franz take the roles of her bloodthirsty kidnappers:

Then the robbers seized the cheiftan's sleeping wife and dragged her through the jungle to their camp. With war-like yells she was bound to the stake. She endured this without complaint, but waited for death with bowed head while the villains discussed cannibalism.

"I'll eat her legs," said Karli, noisily sharpening the knife on a stone.

"They're for me," replied Franz.

"She's got two," said his fellow-cannibal placatingly.

"What's left over will be pickled and put in the larder," persisted Franz the robber.

"Red Indian larders?" jeered Karl, forgetting his part.

"I like the little toes best." The cannibal conversation started up again.

"Me too," replied Karl.

"I'll eat both, though," shouted Franz. "They're sweet as sugar."

"One each," bellowed Karl, adding a sentiment rare among cannibals, "Equal Rights for All."

Besides the debate here between the Fascist idea that the few people worthy of goods in the first place should stockpile any leftovers, and the Communist notion that everyone should share equally, there is also an uncomfortable undercurrent in this discussion about sharing Manja's body. Predictably enough for a Manic Pixie Dream Girl narrative, it is Manja whose imagination and forceful personality holds the little group together—but the boys' gradual realization, as they begin to hit adolescence, that their society views girls as objects to be possessed by one male only, begins to undermine their solidarity. And Manja isn't just a girl: she's a poor Polish Jew, and she's growing up in a society that is tightening like a noose around people in all three of those categories. The boys around her are all torn between the desire to protect her against the threats of the outside world; the desire to maintain the status quo (the children make a heartbreakingly naive pledge that they will never allow their relationships to change); the desire to reject her as her friendship becomes a social liability; and the desire to triumph over the other boys and "win" her for his own.

These dynamics are honestly interesting, and I think Gmeyner does a good job with them. So too, she evokes with complexity certain of the children's parents—in particular, I was impressed with the character arc of Harry's father Max Hartung, an anti-semitic Jew who neglects his own son while fawning over the more Aryan-looking child fathered on his wife by one of Max's political rivals. Gmeyner often makes Hartung extremely unlikeable, yet never abandons the attempt to depict his thought processes with compassion. And I admit to seeing myself in the person of the intelligent, leftist but largely impotent-feeling Ernst Heidemann, father of Heini, who finds himself facing the horror of explaining to his son why their country is controlled by murderous bigots who reject the principles of equal human rights embraced by the Heidemann family.

Manja also asks some interesting questions about destiny and character-formation. It opens, unconventionally, with the scenes in which each of the five children are conceived. From this opening extends a preoccupation with the extent to which our origins dictate our fates: certainly an understandable question for an Austrian writing in 1938. Franz, for example, is growing up in a cruel household devoid of love, a reality reflected in his conception by rape. His parents are callous social climbers and bigots; does this necessarily mean Franz will be, as well? His struggle to break free of his father's cruelty, not to repeat it, is a difficult one: he sometimes succeeds and sometimes fails. Similarly, Manja is conceived under circumstances of unlikely but genuine human connection which is nevertheless unable to avert death: this seems an extremely accurate harbinger of her life to come. Dr. Heidemann, making the rounds of the maternity ward at night, "had a strange thought":

Supposing that their destinies had been packed away somewhere in the basket, like the red water bottles at their feet? And that one of them could be taken out and another put in its place. All had pink faces with sparse and mostly dark hair which would fall out later, and then more would grow, fair curls or smooth black hair. How much of what they were going to be was already in them? How much of what they would experience later was born with them?

Pressing questions at a time when concepts of inborn racial purity or contamination were gaining ever more ominous prominence in Germany. And indeed, one of the most interesting things about Manja, the primary reason I would recommend it to others, is that, like Irène Némirovsky's Suite Française, this is a novel written in the midst of the events it describes. Gmeyner gives us no easy answers at the end of the novel because the future of Germany and Europe were still very much unclear in 1938, and looked very dark for people of Gmeyner's humanist, liberal bent.

So Manja is a relatively thoughtful, anthropologically interesting example of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl genre, and one I'm glad I read. I have to say, though, that many of the aspects of this genre that reliably grate on me, are also present here. Gmeyner does attempt some depiction of Manja's inner life, but sheer numbers are against her: with four boys to depict and only one girl, Manja's subjectivity perhaps inevitably gets overshadowed by those of her male friends. She becomes an object, either for protection or rejection, especially once outside pressures are threatening her as a Jew. Indeed, once a certain key scene of victimization passes, we hear almost nothing from Manja herself before the end of the book, instead watching as the parents and male children react to what they believe happened to her. To some extent this could be read as a comment on how abuse and violation silence and alienate their victims, but for me it isn't totally effective. The narrative structure seems to reinforce the idea that Manja is more important as an idea than as a person—an idea totally supported by the final scenes.

I mean, don't get me wrong: I shed tears at the end of this book, just like I always cry at the end of Harold & Maude, just like I remember bawling after finishing Bridge to Terabithia as a kid. The MPDG formula is a compelling one: if it weren't, it would hardly be so enduring. There is something satisfying about watching the male recipient of the sacrificed Manic Pixie's joie de vivre walk away from that cliff or that hospital room, a sadder but a wiser, more hopeful man. And yet the formula is compelling at the expense of female subjectivity, of female complexity, of female maturity: an exchange I tire of making again and again and again.

This post on Manja is my contribution to Persephone Reading Weekend, and my first actual Persephone! (Though I did write about Isobel English's Every Eye in a different edition.) Thanks to Verity and Claire for hosting the festivities.