Well, 2010 has been an excellent reading year for me. It started out with a revisitation of one of my favorite authors with Woolf in Winter; reading the posts and comments of so many other people on some of my favorite novels was an amazing experience, and made me feel like the college semester I spent writing about Woolf had an actual, real-life application.

In February I had an intense but contradictory experience reading Julio Cortázar's Hopscotch, which provoked me to write three separate posts (one adulatory, one angry, and one interested), each as long as my regular, already-lengthy entries. I'm still not sure how I feel about Hopscotch overall, but any book that gets me that engaged must have something going for it.

In March, my perusal of Volume IV of the Paris Review Interviews got me interested in several authors I hadn't read before, including John Ashbery, whose Notes from the Air later became a surprise hit with me.

April was a red-letter month. It brought a shared read of Georges Perec's Life a User's Manual, which delighted pretty much all the Wolves involved; the discovery of Lydia Davis's micro-stories in Almost No Memory; and a French-language read of Émile Zola's Germinal, which convinced me that I actually do enjoy naturalism if it's done right. I also got to rip a new one for my old friend Henry David Thoreau; at the time I was worried that I'd offend people with this post, but in actuality it apparently made me some new friends. Who knew?

With May came the conclusion of my Essay Mondays project, in which writing about a different essay every week gave me a nice grounding in the genre and introduced me to some new favorites, including Joan Didion. In June I went on honeymoon to Hawaii, lay on the beach with such fluffy love stories as Alexandr Solzhenitsyn's Cancer Ward, and bought a copy of Cormac McCarthy's All the Pretty Horses containing a note which reads "Reminds me of Garrison Keillor"—still a favorite book-related joke for the year. This summer, too, I finally got around to sampling Shirley Jackson's short stories, and became a firm convert to her gothic, darkly humorous style.

In September I discovered one of my top reads of the year, Simone de Beauvoir's Mémoires d'une jeune fille rangée, whose combination of existential feminism and keen philosophical insight into the author's early development had me practically swooning. October brought Frances's three-part Madame Bovary readalong, which left me impressed with Flaubert's keen powers of prosody and observation, but irked at his smug world-view. Flaubert did teach both Richard and me the vocab word redingote, which will come in very useful the next time we want to buy frock coats in Paris.

Meanwhile, the clear highlights of my reading in November and December were both Anne Carson projects: Nox, a beautifully-packaged, thoughtful and heart-wrenching elegy for the author's dead brother, and An Oresteia, her breathtaking translations of Aiskhylos, Sophokles and Euripides. I'd say An Oresteia ties with Simone de Beauvoir (and Woolf, of course) as my Best Book of 2010.

Speaking of Beauvoir, I read five books in French this year, which is four more than last year, and included the somewhat difficult Flaubert. I feel very good about this! I can feel my French getting better all the time as I garner a better sense of the language's flow and build my vocab. I'll be reviewing Irène Némirovsky's gorgeous Suite Française shortly, and in 2011 I hope to read at least one novel in French every month. We'll see how I do with that goal.

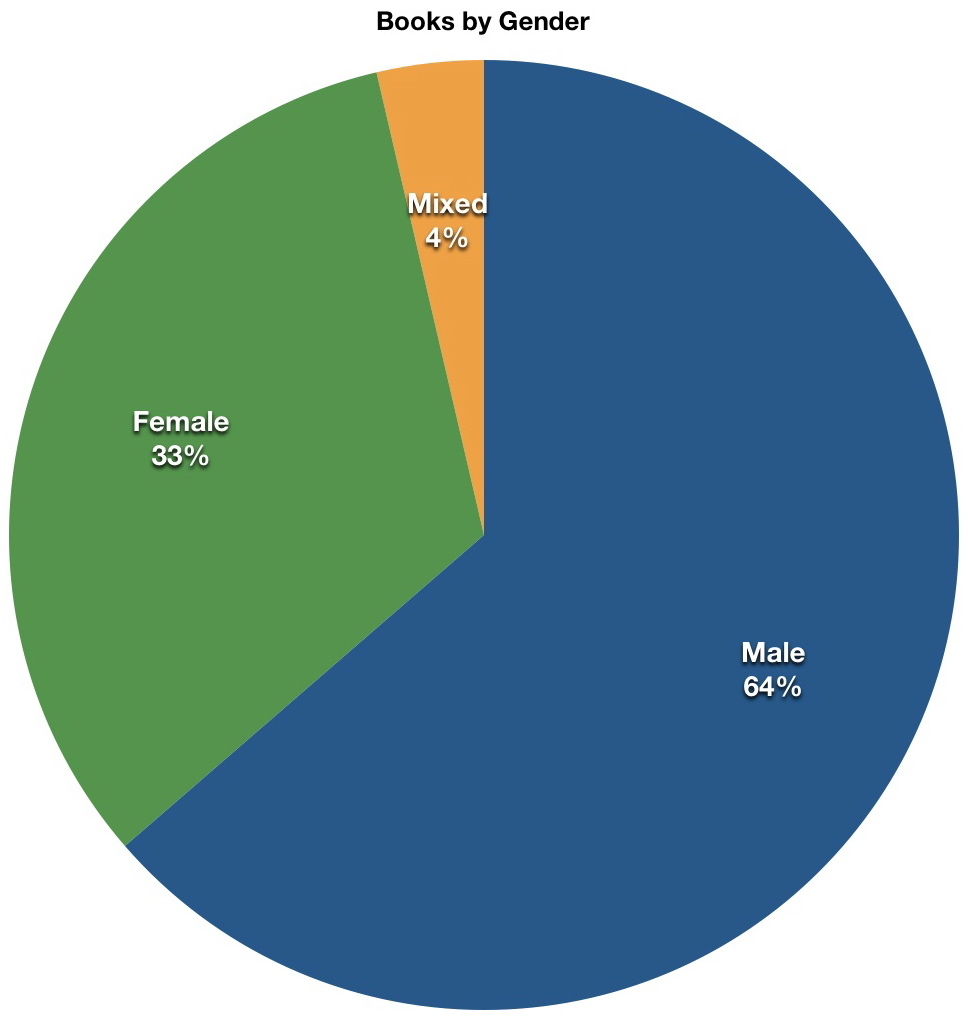

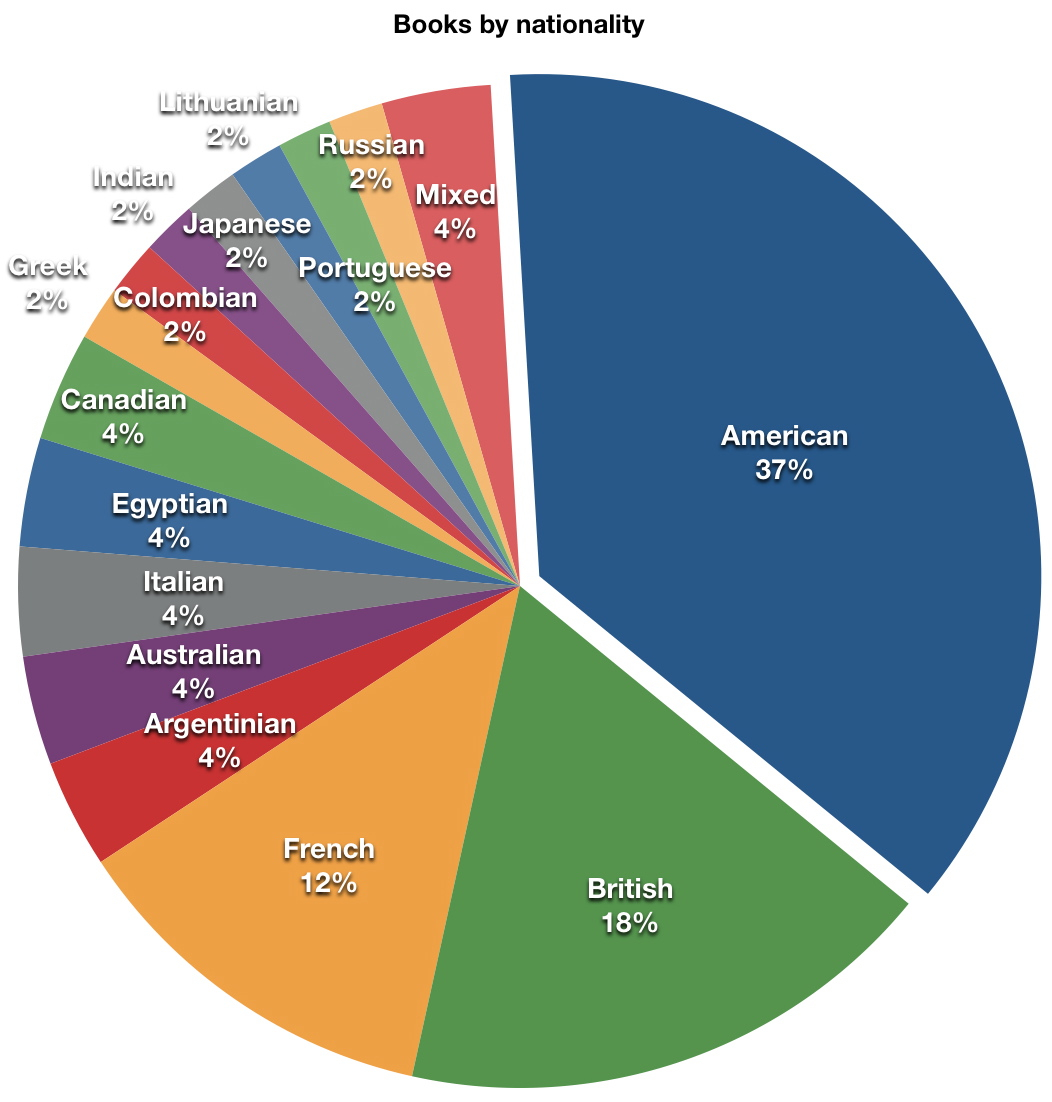

And now, onto the flashy stuff! (Click any pie-chart to enlarge. Also, if total percentages don't add to 100, blame rounding.)

Firstly, a breakdown by author's gender: obviously, there's about a two-thirds to one-third predominance by male authors in my 2010 reading, and one of my goals for 2011 is a more gender-balanced reading list. (FYI, the "Mixed" category in all these charts refers to anthologies with contributions from different genders/nationalities/regions.) I think it's telling that, although I read twice the number of books by men this year as books by women, my year-end highlights above feature an almost exact gender split, which I take as a sign that it's time to seek out more books like the Carson, Beauvoir, Woolf, Didion, Némirovsky and Jackson that so impressed me in 2010.

A breakdown of 2010 reads by author's nation of origin (or main country of residence, in some cases) shows a clear domination by American, British, and French titles (67% collectively), but with a decent spread throughout the remaining 33%. Every continent except Antarctica is represented, although in some cases only by one or two countries/books. In 2011 I'll definitely be expanding the French section as I prepare for, and then recover from, David and my trip to France in May and June, and I also hope to pick up some books on that trip by francophone authors from Africa and the Caribbean, regions where my reading was almost nonexistent this year. Marianna Ba and Véronique Tadjo are at the top of that list, but I would also welcome suggestions! (Keep in mind that I'm not a huge fan of magical realism.)

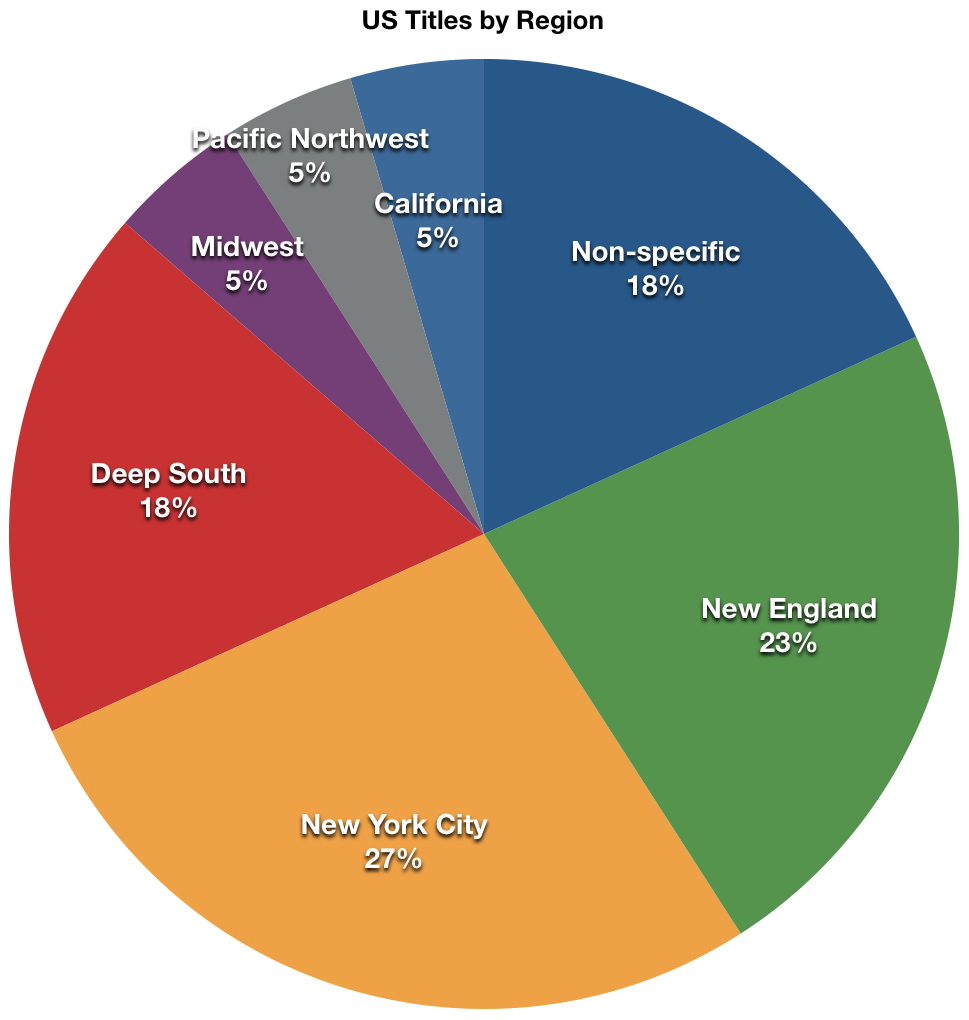

Because the US (my own country of origin) is so gigantic and diverse, I thought it might be interesting to split that big blue wedge further, into regions. I often think the various regions of the US are more different from one another than many contiguous countries.

There is something surprising about this breakdown. Regular readers, have you spotted it? That's right: NEW YORK CITY. In case you're new here, I don't care about New York City. I have have never found myself susceptible to the interest or romance of it the way I have with London or Paris—or hell, even San Francisco. When I visited, the highlight of my trip was spending quality time with my mom, and going to the amazing medieval art museum at The Cloisters—whose defining characteristic? Is that it's outside the city. People, one of my best friends moved to Manhattan over a year ago and I have not visited her. Yet somehow, 27% of the American lit I've read this year has been New York-centric. This must change. My resolution for American lit read in 2011 is to focus on Southern Regionalist and Western authors, and take a break from the New Yorkers for a while. (Ironically, The Wolves' first 2011 selection is set in New York, but that's okay! I'll just stick to that one book and not read (m)any others.)

So, to recap, goals for 2011:

- At least one book in French every month;

- More female authors;

- More francophone authors from African and/or Caribbean countries;

- Fewer authors from/books set in New York City, to be replaced with those from the Deep South and the West.

I think I can handle that!