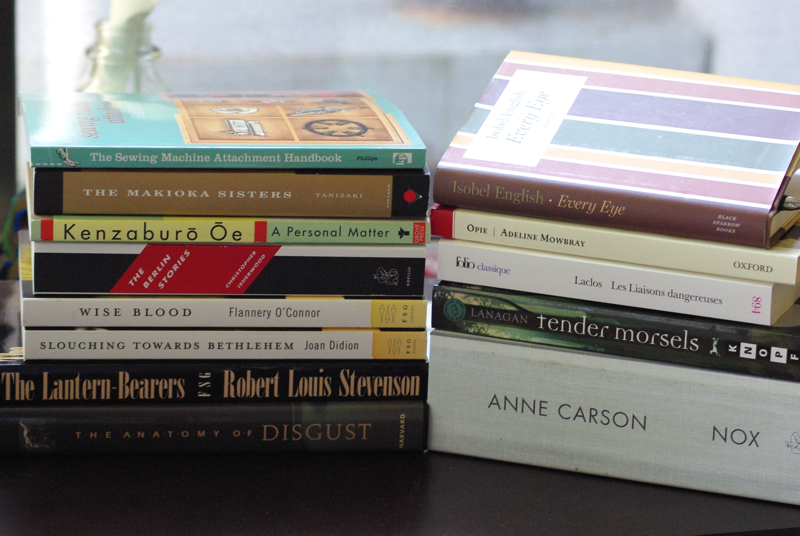

More than any book I've read lately, Margo Lanagan's Tender Morsels (a re-telling of the Germanic fairy tale "Snow White and Rose Red," and also an examination of the powers and limits of coping mechanisms after a severe trauma) took me outside my reading comfort zone. For one thing, it is marketed as a "young adult" novel here in the States, a classification I don't normally read. For another, it involves elements—parallel dimensions, witches and sorceresses, people transforming into bears and back into people—that mark it as fantastical, and not in a wacky Japanese dream-world way or a surreal David Lynch-type way, but in an undeniably—well—Fantasy type way.

And that, I'm ashamed to say, kinda freaked me out. I'm not claiming it's good or it's right, but there you have it. I am prejudiced enough to have cringed over the more involved magical scenes. Moon-creatures hovering over abysses, witches conjuring portals between two parallel worlds; sorceresses explaining to rooms full of people how this and that magical mechanism functioned—I must admit it gave me pause. I was reliably more engaged whenever Lanagan veered toward the classic "fairy tale" format—iconic rather than developed characters, magic that seems more about allegory than magic-for-magic's-sake, schematic events that move quickly and use a certain, specific kind of heavily simplified language ("Once upon a time, in a cottage at the edge of a forest, there lived a young girl and her brother..."). Certain scenes in Tender Morsels really tapped into that rich, allegorical power that fairytales can have. I got chills during the scene when Liga realizes, after being incestually abused and then gang-raped, that her town has mysteriously been transformed into something that will not hurt or threaten her anymore:

Lucky indeed Liga felt, walking home that day with figs and sugar and good smoke-meat in her basket, and her first lesson with Mistress Taylor set for next afternoon. It was all very different from the noise and bustle and nastiness she had expected to weather in the town; it was very odd to have conjured a headful of terrors and carried them into St. Olafred's, only to discover them all to be unfounded.

She held her baby close against her breast as she walked along. "How lovely, Branza! Such a different place! How long can it last, do you think? Is it to be ours forever?"

This scene reminded me of the final pages of Toni Morrison's The Bluest Eye, in which Pecola reacts to her father's rape by retreating into a fantasy world where she has achieved her life-long dream of being blue-eyed and having a friend. From the outside, however, it merely looks as though she's walking around talking to the air, flailing her arms like a broken bird. There is a disconnect between perception and reality: suddenly Liga's world is much safer and kinder, her emotions calmer; to her, this is a sign that the harm against her has been magically alleviated, whereas to the reader it's an indication of just how extreme that harm really was.

What I'm getting at by beginning my post with the ways in which my snobbishness sometimes got in the way of my enjoyment of Tender Morsels, is that the novel deserves so much better. Although I wasn't completely riveted at every moment (for a fairy tale, the book is quite long), although it's not up my normal alley, Lanagan's story gave me so much to unpack. It speaks eloquently about the ways in which the richness of life is inextricably bound up with the tragedy and hurt of it, and about how people can reach a point of hurt where their only feasible survival strategy is to cut themselves off from that richness, retreat into a flat safety. So too, it raises fascinating questions about the process of emerging from places of safety—both for the person (in this case Liga) who created the retreat in the first place, and for those (her daughters) who have never known any other reality. On the one hand, Lanagan seems more optimistic than Morrison: we get the sense that Pecola will never emerge from her shattered madness, whereas Liga is pulled from her retreat after twenty-five years, and learns to live in the world and even appreciate what it has to offer. On the other hand, we are also left with a sense that, in certain ways, she has waited too long: by savoring her retreat for so many years, she has permanently missed some of the fullness of real-world existence. She emerges at age 40 with only an adolescent's understanding of certain aspects of life, and it's too late to recoup her losses completely. This seems to me an accurate, if tragic, comment on the experiences of many people with severe trauma early in life: they simply never get the chance to catch up.

Lanagan makes several decisions in Tender Morsels that seem ripe for discussion, and which I didn't completely understand. For example, the narration in the novel switches between third-person (in sections dealing with Liga and her daughters, Branza and Urdda) and a variety of first-person narrators—the rascally but charismatic dwarf Collaby Dought; earnest Davit Ramstrong, who spends three months with Liga as a bear; young Bullock Oxman, who becomes a bear in his own world, against his will. Although Lanagan is plainly interested in the female experience in this novel, it's hard not to notice that all of the characters who actually get a voice here are men. Not even the cackling widow Annie Bywell speaks for herself directly out of the page. Lanagan herself says, in the book's appendix, that she

wanted to make a subtle point about how the men are comfortable imagining themselves as the heroes of their own story, whereas the women always feel themselves to be part of a bigger story that is more significant than their own lives.

I find this explanation unsatisfying. Yes, it is part of male privilege to feel one is the hero of one's own story. But the particular female characters Lanagan creates—in particular Annie, who is selfish and strong-willed enough, certainly more so than Davit Ramstrong, and also Urdda, who has a child's self-centered curiosity until very late in the novel, and who has been raised in a dream-world with her mother at the center, away from patriarchal power structures—I don't believe they think of themselves as more acted-upon than acting, nor that they necessarily see themselves as parts of a larger whole.

I felt the division of narratives works better as an indication of Liga's alienation: how she is, for much of the story, so cut off from her own self and the world around her. The first-person narrators achieve a level of visceral reality that's absent from the third-person sections, which makes sense given that Liga and her daughters are living in a flattened, passionless world. This, for example, is one of my favorite passages from Dought:

There was a certain type of rich feller liked to use me much as a doll is used, to dress me up in tiny clothes and have me pop up around his house, spreading scandal and scampery. And many a year passed in this merry type of employment.

But I put all of my eggs in one basket with one lord, and off he went and died, didn't he? And what I thought I had coming to me through him, his family felt I ought not to gain—for certainly I had done as he said very well, and their names were all muddied about the place most satisfactory. I got barely a worm-squidge out of them. By dint of being inscrutable, though, I built and built that squidge up, to the point where it all exploded around me in a mess of thieves and cheaters—myself included, I don't deny that—and bills for liquors I and my fellows had drunk but not paid for, meals unremunerated that we had long since shat out.

Liga and Branza, and even Urdda, never get to be quite as vivid as Collaby is here; I kept waiting for the point, after their reentry into the real world, when one of the female characters would assume the first-person voice, but it never happened. I'm torn between thinking this is a fitting statement about the alienating effects of their experiences, individually and as women, and being disappointed because it seems at odds with the more optimistic futures that await Branza and Urdda, not to mention the entire lived reality of Annie.

Another interesting portrayal, I thought, was Urdda's reaction when she learns the truth about her conception. She's utterly devastated, in a way that's made even worse by her earlier sheltered life: she hadn't ever considered that such cruelty and ugliness could exist in the world, much less that it would have engendered her own body. I thought about Kazuo Ishiguro's Never Let Me Go, and how the society in that novel is insidious in exposing the children very gradually to the knowledge of their eventual fates. Kathy says that they are always told just slightly more than they can fully understand, so that no revelation ever comes as a shock. Urdda's situation is the exact opposite: most people, I think, learn about the theoretical possibility of violence and rape gradually, and come to accept (for better or worse) living in a world that includes those things, whereas Urdda has been completely sheltered from anything resembling such knowledge, so that when it bursts upon her in a single torrent she is completely overwhelmed with rage and lust for revenge. It's such an understandable and inevitable reaction that I found myself trying to remember when I myself had felt like that: surely, there must have been a time? My own initiations were closer to those in Ishiguro's novel, however, than those in Lanagan's.

But when Urdda finally gets her revenge, almost without meaning to...I'll just say that I felt Lanagan was inserting a bit more fairy-tale quality into the "real world" of her story. Urdda is consumed with rage, and causes her revenge; after the revenge, she wakes up "with no particular feelings at all" about the knowledge she gained the day before. Her inadvertent act of revenge seems to have slated her anger in a way I found allegorically unconvincing. Is it supposed to be part of the magic of the situation that Urdda has come to complete apathy or acceptance (which is it?) of humanity's violence to humanity, and her own subjugated state as a woman, in the space of a single night? Is this change of feeling engendered by violence? I find it hard to believe that any simple act of retribution could really slake such a deep hurt. Is there some kind of key in the fact that the violence Urdda causes is unintentional, or righteous? Either idea strikes an uncomfortable chord in an otherwise beautifully resonant book.

Tender Morsels was our May read for the Non-Structured Group; June's pick is Gabriel Josipovici's Moo Pak. Discussion on the 25th; feel free to join in!

I'm also counting Tender Morsels as my third book toward the Women Unbound Challenge.