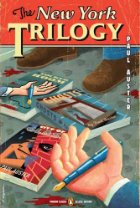

As I could feel myself coming down with my partner's cold on Wednesday afternoon, I rushed into the bookstore to pick up a birthday present for my dad, and there was the beautiful Penguin Classics edition of Paul Auster's New York Trilogy, marked down a tempting thirty percent. It was the right time for this book, my friends, and the universe offered it to me as compensation for spending the next two days groaning and snuffling on the couch. The three novellas - City of Glass, Ghosts, and The Locked Room - are my definition of perfect home-sick-from-work reading: literary, metafictional takes on the private eye genre, they evoke that familiar noir-ish atmosphere while at the same time weaving in enough off-kilter ambiguity, rejection of plot resolution, and what my friend Alan would call "thinky-ness," to keep things interesting for an inveterate thinky-pants like yours truly. I won't go so far as to say it made me happy to have come down with a nasty head-cold, but it definitely helped me to bear up with good grace.

All three of these novellas are detective novels concerned with books, writing, and writers: writers mistaken for detectives, detectives staking out writers, writers of detective novels impersonating detectives, writers who disappear under mysterious circumstances that lead other writers into investigating their disappearances. Auster reminds me irresistibly of Roberto Bolaño in the way that discussions of literature, and of the acts of reading and writing, are seamlessly incorporated into his text in ways that are delicious fun to read. In most cases, too, literary conversations between characters come to be mirrored in the structure of the book itself: never does Auster forget that what his reader is holding in her hands is an artifact, an object capable of explaining and referring to its own existence. The first novella, City of Glass, for example, begins with a triple-screen: the novelist Daniel Quinn, writing detective fiction under the nom de plume William Wilson. Wilson's private-eye investigator is named Max Work, and Quinn is starting to feel that the detective Work is taking up more and more of his consciousness. Then Quinn starts getting mysterious calls in the middle of the night, and the caller is looking for a private detective named...Paul Auster. I think, at this point, you are either tickled by the novelty or disgusted by the cleverness.

It's always a daring move for an author to insert himself into his own fiction. Sometimes it's a total turnoff for me, but I thought Auster handled it well: he had already built up such a self-reflexive series of identities for Quinn/Wilson/Work that doubling all the way back around and having Quinn be mistaken for his own author is, I think, delightful. He's constructed a situation where we have an author writing a detective novel about an author of detective novels, who is mistaken for a detective who is, in actuality, not a detective but an author. For Quinn later tracks Auster down, and he's not a private eye; he can't explain why he should have been taken for one. He does sit Quinn down, though, offer him an omelette, and regale him with a complex, circular theory about the novel Don Quixote. The book we take for a novel by Cervantes is, argues Auster-the-character, a legitimate artifact: Cervantes really was approached (as the text claims) by someone in a bazaar, ostensibly an Arab who was the real author of the work. In reality, Auster-the-character goes on, this person was Don Quixote himself in disguise: he had feigned madness and concocted an elaborate con on Sancho, the barber, and Samson Carrasco, basically orchestrating the events in the novel and manipulating his three friends into creating the manuscript in order to ensure his reputation would live on in perpetuity. Quinn and Auster-the-character begin this conversation by narrowing in on Cervantes's preoccupation with verifiability:

"It's quite simple. Cervantes, if you remember, goes to great lengths to convince the reader that he is not the author. The book, he says, was written in Arabic by Cid Hamete Benengeli. Cervantes describes how he discovered the manuscript by chance one day in the market at Toledo. He hires someone to translate it for him into Spanish, and thereafter he presents himself as no more than the editor of the translation. In fact, he cannot even vouch for the accuracy of the translation itself."

"And yet he goes on to say," Quinn added, "that Cid Hamete Benengeli's is the only true version of Don Quixote's story. All the other versions are frauds, written by imposters. He makes a great point of insisting that everything in the book really happened in the world."

"Exactly. Because the book after all is an attack on the dangers of the make-believe. He couldn't very well offer a work of the imagination to do that, could he? He had to claim that it was real."

"Still, I've always suspected that Cervantes devoured those old romances. You can't hate something so violently unless a part of you also loves it. In some sense, Don Quixote was just a stand-in for himself."

"I agree with you. What better portrait of a writer than to show a man who has been bewitched by books?"

By the end of the conversation, then, Auster-the-character is arguing that Cervantes is offered a faked manuscript by a person who is, in some way, a stand-in for himself, and going on to insist on this story in order to prove that the faked manuscript is, in fact, real. Which turns out to be unnecessary, since the events in the book actually did take place, just not for the reasons that the writers (and Cervantes) believed. Which in turn means nothing, because even though the events took place, they were intentionally manipulated, so that Cervantes inherits a faked manuscript (faked by Sancho et al) which is a genuine chronicle of faked events (faked by Don Quixote), from a man who may or may not be just another version of himself. Not only that, but by the end of City of Glass we find out that the text we have been reading is similarly an artifact, similarly at many removes, and similarly preoccupied with obsessive adherence to "verifiable" facts that, nevertheless, were sketchy to begin with.

This kind of game delights me, although I can understand if it doesn't delight you.

I found Ghosts to be the weakest of the three novellas (although still quite enjoyable), with The Locked Room reminding me, unexpectedly, less of Bolaño and more of Kazuo Ishiguro's typical detail-obsessed narrator, haunted by demons from his past. All three books really should be read together in one unit, as The Locked Room ends up shedding new light on the events of the first two books, twisting their context and making the reader double back on herself to figure out what exactly happened. True to postmodern form, it all almost makes sense in the end...but not quite. For someone like me, who dislikes any mystery whose ends are tied up any tighter than those in, say, Chinatown, this was just right.

I have to say, though, that as much as Auster's sparkling literary cleverness and smoky retro atmosphere reminded me of Bolaño and Ishiguro, I didn't find in this trilogy the same greatness of soul possessed by the other two writers. Despite the darkness in both their works, Bolaño and Ishiguro both address the human capacity to continue on and create meaning for themselves in the face of horror. Auster's only comment on the human experience seems to be that we're all a hair's breadth from descending into madness and non-meaning - true as far as it goes, which is not that far. This didn't bother me - I think a certain amount of nihilism is to be expected even from mainstream noir, and that much more from a postmodern deconstruction of the genre - but it means I didn't think Auster's content quite lived up to his style in this particular instance. That's okay, though - not every book needs to present an entire philosophy of being. As I said, the nihilism fits the genre, and there were more than enough compensations to make this a highly enjoyable read.

Everybody I know/respect (*everybody = you, Frances, and about three other trusted bloggers from the Spanish-speaking world) who have actually read Auster all love him, Emily, but I have to say that The City of Glass just left me cold. For me, the cleverness you mention came off as Auster being too impressed with his own cleverness or something--although there were parts of the game that I did enjoy (many discussed in your fine post). The story itself just didn't grab me. I'll finish reading the rest of the trilogy one of these days, and I hope it picks up because I do love that cover and don't really want to part with it! P.S. Enrique Vila-Matas and Auster are apparently fans of each other's work, so you should scope out some of their joint interviews and such when/if you ever get around to reading that copy of Montano's Malady you picked up a while back. Might be an interesting diversion!

Oh this is one I really want to read! Everything I've read by Auster, I have loved. I think that the nihilism you speak of is not necessarily present in all of his works. Especially not in The Man in the Dark - there definitely were aspects of the humanity and a redemption of sorts. I think you would really like Man in the Dark and The Book of Illusions. Both were wonderful, but at the time when I was reading them I wasn't so sure. Somehow, though, they've both stuck with me. The Book of Illusions I read several years ago, but it's still one I think back to regularly.

I've heard rumblings about Auster and cheers and jeers for this book. I never knew what it was about. Now I do and oh, it sounds yummy! I'm going to have to get myself a copy now. I hope your cold is all better.

I've read several Auster books, though this one is still in my TBR Land Mass. My problem with Auster is that he's a great stylist, he knows his techniques, but--and I'm saying this as true as I possible can--he just doesn't have heart. At least, he doesn't even try to take stab at mine. There's a cold calculation to his greatness, in my experience with him.

Which is not to say that I won't eventually pick up this book and dust it off. Eventually. :]

Richard: I can totally understand your reaction. The whole time I was reading, I was thinking "If I had started this at a different time/in a different mood, it would have struck me as horribly self-satisfied." As it was, it happened to catch me just at the right moment and I heartily enjoyed it. I think that, having just revisited Mrs. Dalloway (which is my "heart" novel), I could handle Auster's soul-lnessness and enjoy his head games.

Lu: Interesting that others of Auster's works come off as less nihilistic! I definitely plan to read other works of his when I'm in the mood for his particular brand of stylish cleverness...I'll definitely check out the two you recommend. Thanks for the tip!

Stefanie: Cheers and jeers, indeed! Practically all the ratings on GoodReads & LibraryThing are either 5 stars or 1! I think it's quite enjoyable if you have a specialized set of tastes. :-) And thanks for the cold well-wishes...it's still hanging on, but I'm on the mend.

Sasha: Yes, I would agree that he's pretty heartless/soulless. I couldn't get by on a steady diet of Auster, for sure - not very nourishing. But as the occasional injection of shiny, playfully dessert-like nihilism, I think I can quite enjoy him. Thanks for stopping by, btw!

I almost picked this up for my birthday last month, but decided on The Corrections instead, though do plan to get the pretty copy one day. :)

I have Moon Palace on the tbr, have not read anything by him yet, so it'll be a surprise.

William Wilson! That's an Edgar Allen Poe story about doubling and doppelgangers! Sounds like Paul Auster did it on purpose.

Claire: It is definitely a temptingly pretty copy. And the cover is so tactile that, if nothing else, you'll enjoy holding it in your hands for the length of time it takes to read the book. I'll be curious to see if you like him or not!

EL Fay: Oh. my. God. The meta never quits!