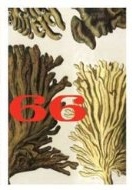

My readalong friends! Even though I turned the last page of 2666 and wrote the following post several months ago, I've been putting off publishing it because of my sense of loss at this fantastic readalong finally ending. The book alone would have been a great ride, but meeting all of you and having our discussions...let's just say, I feel lucky to have stumbled into such a special reading experience. And I'm psyched that so many members of our group will be meeting again for Kristin Lavransdatter, yet it's still a little sad to be saying goodbye to Bolaño. But enough sentimentality! Here's what I wrote after finishing 2666 all those months ago.

There's a lot of talk, in bookish circles, about "circular narratives": stories that take the reader on a journey, only to return, in the end, to the point of departure, imparting in the process a new perspective. Roberto Bolaño's 2666 also returns to the point of departure, to "the scene of the crime," as one character puts it. In many ways, The Part About Archimboldi deposits the reader back in the world of The Part About the Critics: a European world, insular, preoccupied with the struggle between nationalism and cosmopolitanism, and preoccupied with literature - preoccupied, in particular, with Benno von Archimboldi, the elusive novelist pursued by the critics of the first part, and here followed from his seaweed-obsessed boyhood, through his service as a soldier during the Second World War, and into his old age. Toward the middle and end of the fifth part, we even find ourselves back behind the scenes of the literature machine manned by Mr. and Mrs. Bubis, as we witness interactions at the publishing house and in the salons of literary critics. Once again we are treated to the light, satirical touch that characterized The Part about the Critics. (One of my favorite satirical passages of the fifth part concerns a woman at a dinner party whose unhappy expression escaped no one

"except Willy, the other literary critic, whose specialty was philosophy and who therefore reviewed philosophy books and whose hope was someday to publish a book of philosophy, three occupations, if they could be called that, which made him especially insensitive to indications of the state of mind (or soul) of a fellow diner."

There wasn't too much of this kind of high-brow ribbing in The Part About the Crimes.)

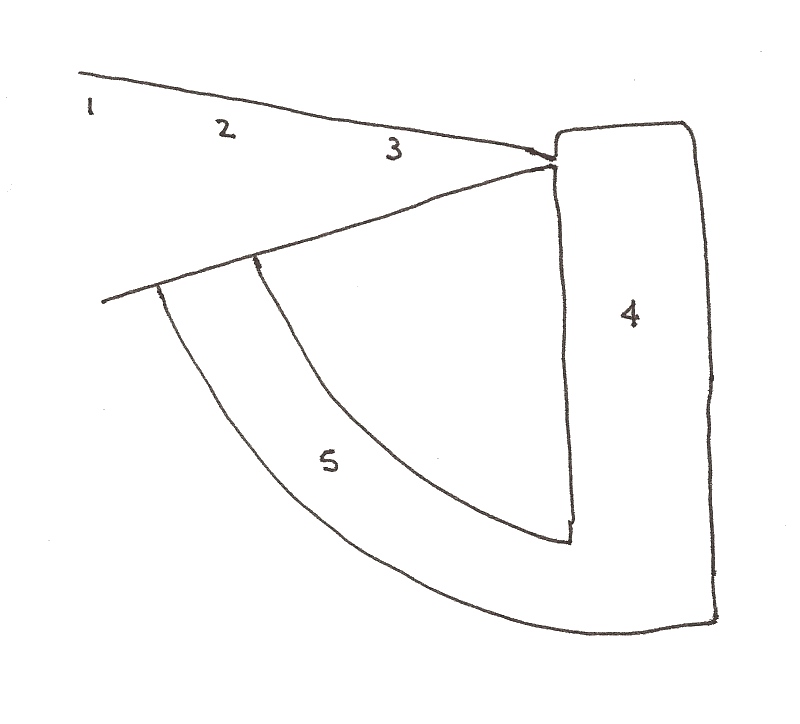

Nevertheless, I wouldn't describe the structure of 2666 as circular. In fact, I'd say it looks more like this:

The first three books tighten into an ever-more tense and surreal vortex, narrowing uncomfortably toward the mysterious wrongness in Santa Teresa, Mexico, which is related to the sexual homicides being committed there. Just as the third part reaches a climactic pinhole, the narration suddenly widens, becomes a stark, straightforward descent through a pile of dead bodies, the hardboiled chronicling of the female corpses of Santa Teresa, and of the inability of police, private citizens, detectives and seers to stop the perpetual appearances of more. As opposed to the increasing tension of the first three parts, I experienced the fourth part to be even throughout, tension released and stark reality confronted. Then, in The Part About Archimboldi, the narrative turns a sharp corner into something more like a traditional bildungsroman, in which a young boy grows up, lives his life and finds his calling: a calling which gradually curves toward the literary world of the first part, and a life which, even more tangentially, intersects with the Santa Teresa killings.

I can't decide to what extent I feel the loose ends are tied up as 2666 draws to its close - nor am I sure to what extent I want them to be. Surely, given the still-unsolved nature of the Juarez crimes on which those in Santa Teresa are based, it would seem wrong to provide an easy answer to the central, unanswered questions: what is the truth behind the killings? Who is responsible for them, and what has gone so horribly wrong in this person's mind and the world outside it? Maybe it's not possible to answer this last, despite the tidy endings of most detective novels: how to locate the ongoing sickness that makes humans engage in extreme violence, whether the atrocities of war, the mutilation of female factory workers, or the savage beating of a sexist taxi driver?

The whole of 2666 brings the world of reading and writing into contact with the world of violence, and it seems to me that they coexist, without negating each other. It doesn't seem to me that 2666 is asking "What is the point of art in such a fucked up world?" Often, this is the way the debate is framed, as if art must somehow overcome the world's darkness in order to validate itself. Bolaño, on the other hand, lets them exist simultaneously, each on its own terms. It doesn't seem to me that literature or art, in Bolaño, can rescue a person from violence or explain the violence away. Art doesn't even necessarily engage with the violence - the book that alleviates the tedium of Barry Seaman's jail time, for example, An Abridged Digest of the Complete Works of Voltaire, has little to do with the race-motivated violence that landed him inside. In fact, the title of this book is so odd-seeming that Oscar Fate remembers it later and laughs about it. But Seaman argues that reading - reading just about anything, he seems to mean - is an inherently useful activity:

Reading is like thinking, like praying, like talking to a friend, like expressing your ideas, like listening to other peoples' ideas, like listening to music (oh yes), like looking at the view, like taking a walk on the beach.

In other words, reading is a way of living one's life, a way of bringing oneself into contact with the vast vitality of existence. And some way of being present in one's life is necessary for survival, regardless of the rest of one's environment. Or maybe I should say it is an indicator of survival. I wouldn't go so far as to claim that The Part About the Crimes, the only section of the novel in which nobody seems to read anything (policeman Epifanio is even amused when his young protegé Lalo Cura asks if he can bring home some outdated detection manuals lying neglected in the Santa Teresa police station), owes its plethora of corpses to the conspicuous absence of books. But the two could both be symptoms of that underlying wrongness. And the underlying wrongness could be a lack of presence on the part of some person or some group of people - people who are not, to use Seaman's language, thinking, praying, talking to friends, expressing their thoughts, listening to other peoples' ideas, listening to music, looking at the view, walking on the beach, or, indeed, reading, but existing without presence in a void of destruction. Indeed, one of my favorite passages in the entire novel contrasts this destructive void with a compassionate, imaginative act not unlike reading:

"His name was Dmitry Verbitsky," said the one-eyed man from his corner, "and he died fifty miles from Warsaw."

Then the one-eyed man shifted in his chair, pulled a blanket up to his chin, and said: our commander's name was Korolenko and he died the same day. Then, at supersonic speed, Ansky imagined Verbitsky and Kerolenko, he saw Korolenko mocking Verbitsky, heard what Korolenko said behind Verbitsky's back, entered into Verbitsky's night thoughts, Korolenko's desires, into each man's vague and shifting dreams, into their convictions and their rides on horseback, the forests they left behind and the flooded lands they crossed, the sounds of night in the open and the unintelligible morning conversations before they mounted again. He saw villages and farmland, he saw churches and hazy clouds of smoke rising on the horizon, until he came to the day they both died, Verbitsky and Korolenko, a perfectly gray day, utterly gray, as if a thousand-mile-long cloud had passed over the land without stopping, endless.

At that moment, which hardly lasted a second, Ansky decided that he didn't want to be a soldier, but at that very same moment the officer handed him a paper and told him to sign. Now he was a soldier.

There are so many details in this epic tome on which I would love to focus, which I'm sure would prove fruitful, but I'm overwhelmed by the sheer quantity of them. I'm intrigued, for example, at the prevalence in The Part About Archimboldi of people talking to themselves (a preoccupation of mine ever since reading Woolf's The Years). It's described as "a common sight" to see people talking to themselves in post-war Cologne, and, later on, Archimboldi is driven by a taxi driver who talks to himself. Merely examining the roles of taxi drivers in this novel could produce an intriguing study, as would contrasting Bolaño's portrayal of reading with his portrayal of writing. And of course, the sexualization of violence would be a fertile theme as well (taken, I thought, in an interesting direction by the naked crucifixion of Entrescu). So too, I would love to examine The Part About Archimboldi through the lens of all the references to detective novels (writing as similar to "the pleasure of the detective on the heels of the killer," for example, or the old woman's insistence that Archimboldi not "return to the scene of the crime") in light of the soul-numbing reality of the Santa Teresa murders outlined in The Part About the Crimes.

But alas, it's not going to happen in this blog entry. I look forward to many re-reads of 2666, and now that I have some experience of the novel, I can pick and choose what to focus on when I revisit it. MANY thanks to Claire and Steph for suggesting this readalong; I've benefited enormously from the book itself, and the act of reading it with so many other smart, perceptive people. Ciao for now, everyone!

Thoughts on Part 1: The Part About the Critics

Thoughts on Part 2: The Part About Archimboldi

Thoughts on Part 3: The Part About Fate

Thoughts on Part 4: The Part About the Crimes

(2666 is my eighth book for the Orbis Terrarum Challenge, representing Chile.)