Ever since my high school boyfriend outed me to my youthful music idol as a slavering fangirl, I resolved to be moderate in my attitudes towards artists whose work I admire. Not that I want to downplay my enjoyment of their art, or affect a "too cool for enthusiasm" attitude. But I realized that day at the indie-rock festival how wrong it was that I was uncomfortable speaking face-to-face with this personable, modest woman, all because I had elevated her onto an unreasonable pedestal. I was unable to relate to her as a person, because my veneration of her got in the way, and I was unable to take myself seriously as a fellow musician, because of my veneration for her art. And that, it seemed to me, was a situation worth avoiding in the future.

All of which is to say: my long-time resolution is being put to a severe test by the novels of Peter Carey.

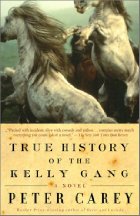

On the plane back from New Hampshire in October, I was practically hyperventilating over the final pages of Carey's Oscar and Lucinda, having to stop after every chapter and decompress for ten minutes before moving on. On the way back from (appropriately enough) Australia, I devoured the entirety of his My Life as a Fake. And now, having just burned through True History of the Kelly Gang, I have to admit to a certain amount of giddy adulation. Carey's consistent ability to create a strong, vital narrative voice; the sheer creative exuberance of his language; the crippling pathos of his storylines and the way his characters grip your heart and won't let go: reading his work is artistically, mentally and emotionally an utter joy.

One of my favorite qualities in a novel is a narrative voice so distinctive that I carry it around with me in my head while going about my business, and Ned Kelly's is a beautiful example. The language and character development here are intimately linked, in a way much more sophisticated than the over-used equation of "writing in dialect" with "uneducated" and/or "stupid." Kelly's unorthodox grammar and punctuation do point, of course, to his lack of formal education, but his style as a whole does so much more, immersing the reader in a wild, hybrid, semi-Biblical landscape that flexes and reels through the narrative, at times becoming so taut that it approaches poetry, yet never seeming unnatural. From his first sentence, Carey had me:

I lost my own father at 12 yr. of age and know what it is to be raised on lies and silences my dear daughter you are presently too young to understand a word I write but this history is for you and will contain no single lie may I burn in Hell if I speak false.

Even in these scant lines, so much of Kelly is present: his anger and his tenderness, his self-justification and his inescapable ties to past and family. And, of course, his religion, for being poor Irish Catholic "currency" (the nominally free offspring of convicts forcibly settled on Australian soil) is at the heart of Kelly's identity and his actions.

One of the many things I love about Carey's novels is how thought-provoking and ambiguous their morality tends to be. From a self-sacrificing love expressed by a gambling addict as a suicidal bet, to a mysterious manuscript whose ownership is so murky that an obsessed collector is left wandering in a morass of half-truth, his characters operate within moral frameworks that are engaged with tradition, yet strikingly unique. Kelly Gang is somewhat less unexpected in its morality than either Oscar & Lucinda or My Life as a Fake - after all, the rise and inevitable fall of the folk-hero outlaw has a well-established canon behind it, from Robin Hood to Jesse James to Don Vito Corleone - but Carey creates a typically nuanced version of the stock character. Rather than taking to crime to alleviate the suffering of the peasantry, or out of dreams of glory, Kelly is born, like all currency, on the edge of the law, and slides gradually over the line under the pressure of poverty, police harassment and family loyalty. At the same time, he is far from a helpless victim of circumstance. Kelly is passionately engaged with his world and his system of honor; the tragedy lies in the radical difference between his understanding of what is honorable, and the definition held by the colonizing English police.

As an interesting take on the outlaw archetype, I particularly liked the scene in which Kelly resolves to start robbing banks. Railroaded into hiding after a police-killing that was two-thirds self-defence and one-third accident, Kelly comes to the realization that the only thing capable of protecting him and his brother from the police are the poor inhabitants of the bush, and resolves to win their sympathies by stealing from the relatively rich and giving to the dirt poor. This is a much more practical, yet still sympathetic, picture of the thought process leading to the Robin Hood mode of operation, than the standard assumption of selfless outrage on behalf of the peasantry. I liked it, and I liked Kelly. I also liked the way in which Kelly's genuine affection for, and identification with, the poor folks he wins over with his bank proceeds grows over time, until we get a passage like this one, a last celebratory hurrah on the evening he learns he is a father:

These was your own people girl I mean the good people of Greta & Moyhu & Euroa & Benalla who come drifting down the track all through the morn & afternoon & night. How was they told of your birth did the bush telegraph alert them I do not know only that they come the men the women with babies at their breast shivering kiddies with cotton coats their eyes slitted against the wind. They arrived in broken cart & drays they was of that type THE BENALLA ENSIGN named the most frightful class of people they couldnt afford to leave their cows & pigs but they done so because we was them and they was us and we had showed the world what convict blood could do. We proved there were no taint we was of true bone blood and beauty born.

Through the dusk & icy starbright night them visitors continued to rise from the earth like winter oats their cold faces was soon pressed through doorway and window and even when the grog wore out they wd. not leave they come to touch my sleeve or clap my back they hitched great logs to their horses' tails to drag them out beside the track. 6 fires these was your birthday candles shining in 200 eyes.

The real star of the show here is Kelly's language, and I admired the way Carey escalates the final tragedy by yanking the narrative out of his anti-hero's hands, to be finished by an antagonist - although, in typical Carey fashion, even that antagonism is tinged with ambiguity.

From first to last, a truly excellent novel, exhilarating and lovely. If we ever go together to meet Peter Carey, you can tell him I said so...just please don't tell him I have Ned Kelly posters all over my walls.

I want to tempt you some more. Try to read this work by Carey (my review follows: http://booksandotherstuff.blogspot.com/2007/06/book-book-review-theft-love-story-by.html)

Thanks for being part of the 9 for '09 Challenge.

Thank you for submitting this review to the Bookworm Carnival, because it led me to your very good blog.

I admit that I did not appreciate this book as much as you did. I thought the writing was exceptionally good, but the story did nothing for me. I am still looking forward to Oscar and Lucinda, though.